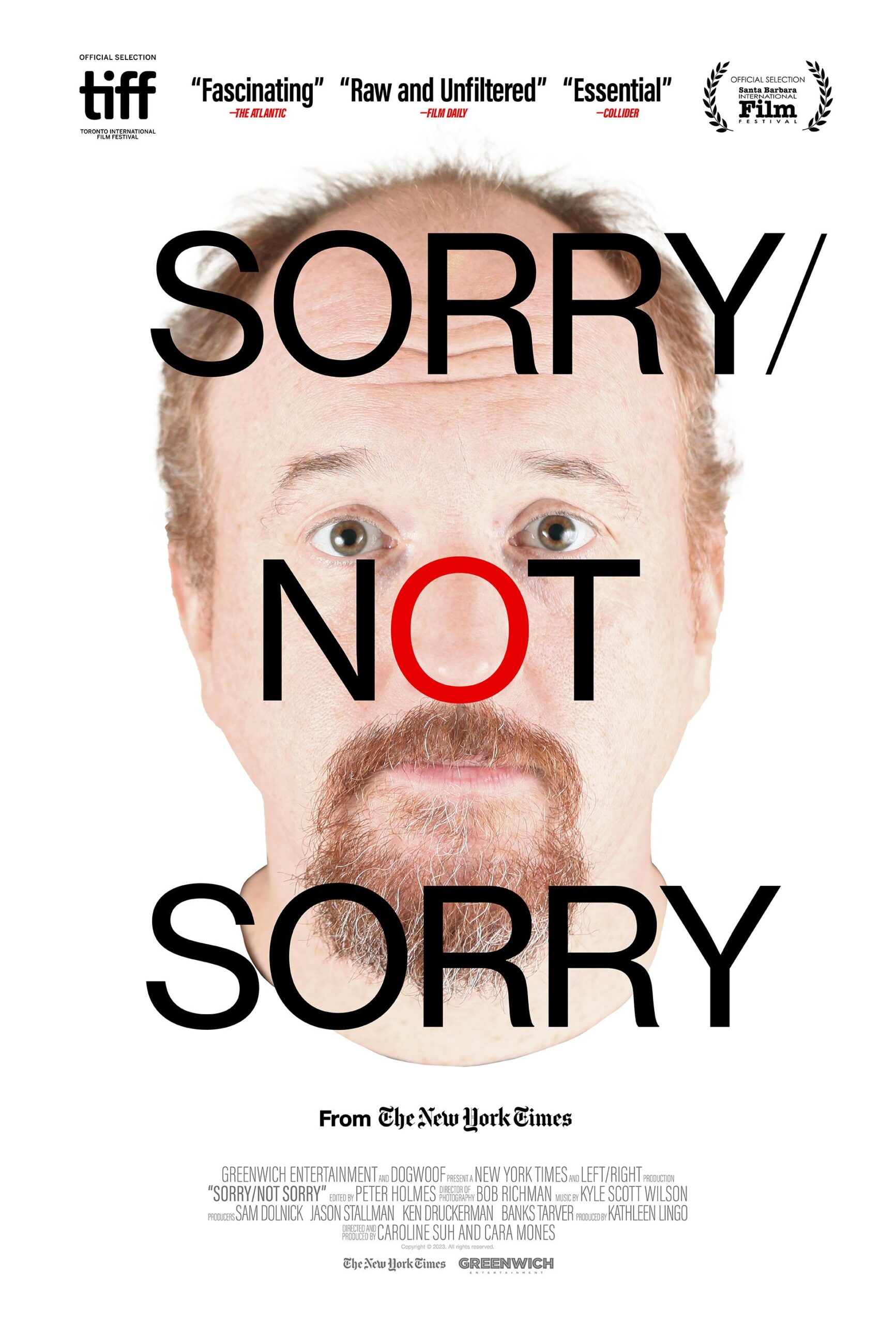

Produced by The New York Times's video division, and depending heavily on its own reporting, "Sorry/Not Sorry" is a primer on the rise, fall and reinvention of Louis C.K. A respected standup comic who remade himself as a low-budget arthouse confessional filmmaker, he became the writer, director, producer and lead actor of the semi-autobiographical FX series "Louie," about a divorced single father who was also a standup comic. At the show's peak of popularity, C.K. was hailed as being the kind of earthy New York intellectual entertainer that Woody Allen's fans used to unabashedly enjoy, before his luster was tarnished by scandal.

Although the movie never convincingly answers the unspoken question that dogs many New York Times-produced long-form videos—"Is this topic better suited to a newspaper article, or perhaps a podcast?"—it is handsomely assembled, with crisp and thoughtful cinematography by Robert Richmond and an insistent underscore by Kyle Scott Wilson that would have fit right into a network TV drama about likable people doing bad things. Co-directors Cara Mones and Caroline Suh try to make the total package as cinematic as possible. They do it mainly by building the story around interviews with women who went on the record with the Times to say that C.K. had abused his power as an A-list club comedian (and later, a king- or queen-making TV producer) by putting them in situations where they felt as if they had to watch or listen to him masturbate or make sexually explicit remarks because if they objected, their careers would suffer.

There are also interviews with C.K. colleagues like Andy Kindler and Michael Ian Black and clips of non-interviewees like Jon Stewart and Sarah Silverman grappling with the knowledge that their friend did something bad and wondering what it says about them if they suspected or knew but didn't act. (Full disclosure: comedy scene chronicler and "Good One" podcaster Jesse David Fox, a colleague of mine at New York Magazine, appears briefly as a commentator.)

The main characters are three comedians—Jen Kirkman, Abby Schachner, and Megan Koester—who experienced that side of C.K. and initially either decided to keep it to themselves for career reasons or were placated into staying quiet. Apparently, C.K. had a habit of forthrightly contacting people he believed had anonymously accused him online and apologizing in a non-specific way or asking if he could talk to them on the phone or meet with them in person (to do damage control). Sometimes, he'd invoke the pitiful specter of his daughters finding out what he did, to shame accusers into backing off.

One of the more confounding and sinister aspects of C.K.'s behavior was that he'd ask people's permission before doing wildly inappropriate things. This created the outward impression of consent, even though the women subjected to his behavior were nowhere near as powerful as C.K. and feared that if they said, "No, I don't want to hear this" or "No, I don't want to watch you masturbate," or just turned and walked away, they'd be blacklisted from everything C.K. was involved in. (Cara Buckley, one of the Times reporters who worked on the piece that nailed down most of the accusations against C.K., says that they solved the problem of contextualizing his behavior by asking whether the same acts would be considered acceptable in a non-showbiz workplace, such as a bank.)

C.K.'s public statement confirming the accusations said pretty much everything a person in his situation was expected to say. It concluded with, "I've brought pain to my family, my friends, my children, and their mother. I have spent my long and lucky career talking and saying anything I want. I will now step back and take a long time to listen."

Did he, though? One of the binding motifs in "Sorry/Not Sorry" is C.K. seeming as if he's not actually seeking forgiveness or making amends, but tamping down the possibility of lasting consequences, in a way that ultimately seems a variation of danger-seeking behavior, where the main goal is to see how far you can push or how low you can go without losing everything forever. C.K. pushed things very far, hid for a few months, then returned to work. If you look at his career through that lens, the post-apology era feels like the ultimate escalation of risk, as well as the ultimate trickster's victory.

In my review of C.K.'s film "I Love You, Daddy," I compared him to a flasher, in that a sizable portion of the perpetrator's adrenaline rush comes from making others doubt that they're seeing what they are indeed seeing because they simply can't imagine that anyone would be so disgusting and blatant in public. In that spirit, "I Love You Daddy" stars C.K. as a father of a nubile daughter who loves wearing bikinis, and John Malkovich as a Woody Allen-like director who becomes her lover. There's also a scene where another character loudly pretends to masturbate and ejaculate in front of a woman in an office.

The movie was shot and completed in 2016 and early 2017, when a contentious election capped by Trump's inauguration and assorted charges of predatory behavior were all over the news, and anonymous accusations against C.K. were swirling around the Internet. The finished film debuted at the Toronto Film Festival in September, 2017, as the Times investigation was being finished, and slated for national release Nov. 17, 2017. The Times piece and C.K.'s confession/apology ran Nov. 9, scuttling the release. The picture painted by "Sorry/Not Sorry" makes you wonder if that two month period was the most anxious of C.K.'s life or the most thrilling. Possibly both? Interviewees express incredulity not just at the movie's timing but its existence. It really did seem as if C.K. was daring people to name the ugliness he was wagging in their faces.

The use of clips of C.K. miming masturbation or sex onstage and in episodes of "Louie" (plus a scene of attempted rape) would ordinarily seem like piling-on or manufactured evidence in a film like this, just as in the "evidentiary" deployment of moments in Allen's films where characters treat pedophilia as a punchline can seem specious and forced even if one believes the worst accusations against Allen. (Put it this way: just because Martin Scorsese's films have a lot of murders doesn't prove he's killed anyone.)

But here, too, C.K. is a bizarrely special case, because you can't argue that he didn't do it. He flat-out said he did it. Every last bit. And you can't say that the women his behavior affected could've easily said no and/or walked away because C.K.'s own statement admits he put them in a position where it was hard to do what should've been done.

The last act of the movie is the most subdued, but also the freshest: after publicly admitting everything he was accused of doing (Times reporter Jodi Kantor says this is a rare case where the subject of an investigation corroborated everything) C.K. reinvented himself as a slightly cuddlier version of a standard-issue, right-wing pandering standup comic—the kind whose act validates grievances against progressives who've "gone too far" and are stifling free speech with their killjoy ways. C.K.'s "listening" period was not long. His comeback is seven years old and selling out arenas. What a singularly weird, gross tale this turned out to be.