On May 27, 1995, Christopher Reeve, who became internationally famous for playing the title character in the original "Superman" movies, was riding at the Commonwealth Park equestrian center in Culpeper, Virginia, when his horse refused to jump a one-meter tall, W-shaped fence. Reeve fell and shattered his top two vertebrae. He barely survived, was rendered quadriplegic and nearly immobile, and would endure severe breathing challenges for the rest of his life. Headlines around the world treated this as a great irony: Superman not only couldn't fly anymore, he could barely move. It was an understandable, well-meaning, but ultimately dehumanizing way to frame it.

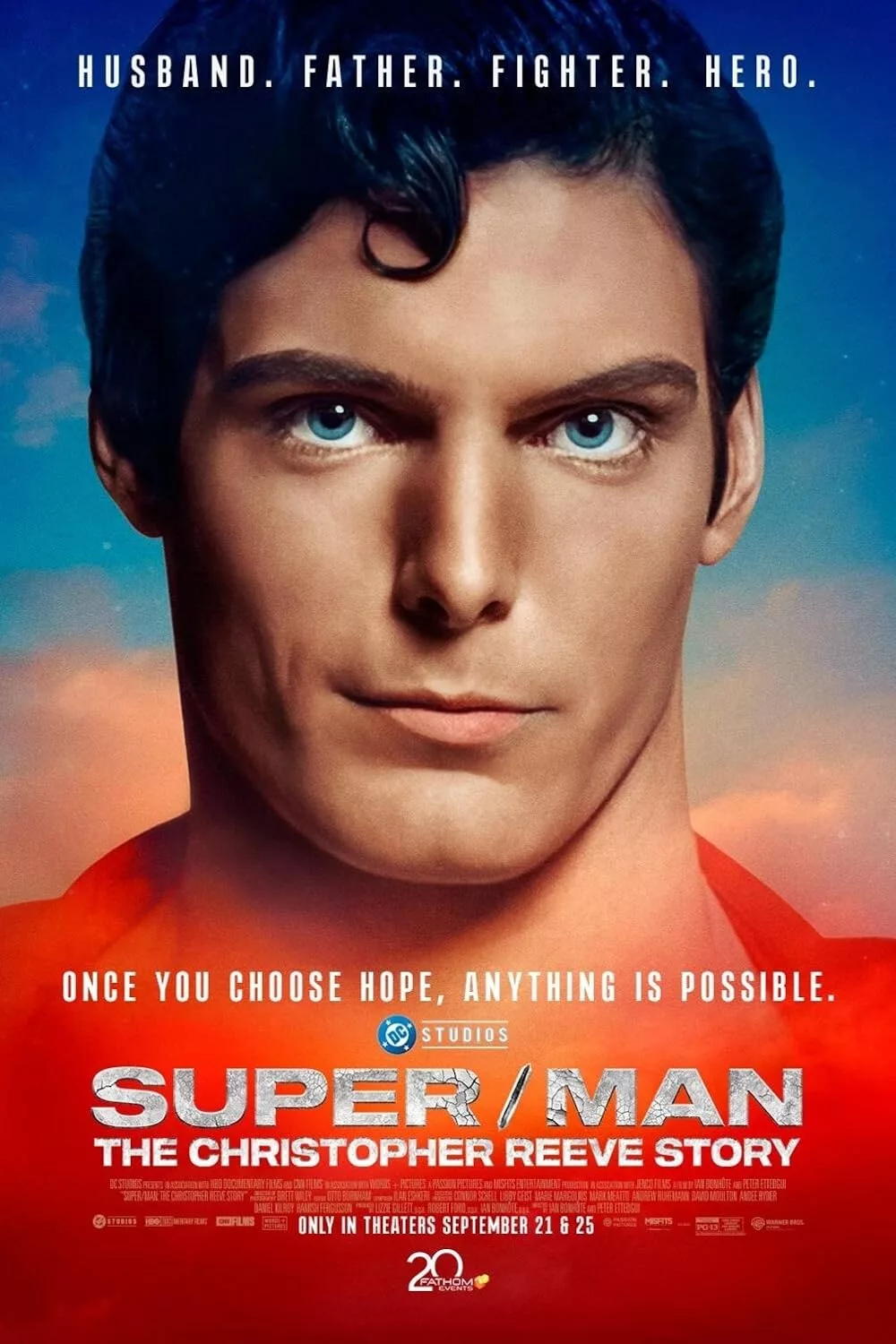

The new documentary "Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story" pushes back against that presentation of Reeve's accident and does its best not to treat Reeve's story as that of a man who had it all but suddenly lost it. It instead presents his life as a story of nearly superhuman endurance and determination: a beautiful and athletic movie star was struck down in his prime, then reconfigured himself as an activist on behalf of people with disabilities. And he would also champion the funding of sciences that might alleviate the suffering of others with spinal cord injuries.

Co-directed by Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui, "Super/Man" doesn't flinch from the blunt physical facts of what happened. But in the end, the approach cements the movie as a work of integrity. It consistently refuses to travel the much easier path taken by previous accounts of Reeve's life: Front-loading his rise to stardom and attempt to move beyond Superman, then presenting his post-accident life as some inspiring postscript (that we don't linger over because it would make audiences sad).

The filmmakers aren't sugarcoating anything here. They're laying out what happened: not just the basic facts of Reeve's life before and after, but the emotional impact on his friends (including his Juilliard acting program roommate Robin Williams, who was like a brother to him); his wife Dana, a super-heroic spouse who took care of him, and inspired and joined his activism; his first two children, Matthew and Alexandra; the kids' mother Gae Exton (Reeve's on-again, off-again girlfriend for a decade); and most piercingly, little Will Reeve, his son with Dana. Will was a toddler when the accident happened and spent his third birthday without his father because Reeve was in the hospital fighting for his life. There are a lot of moving home video snippets in the documentary, but the bits showing that beautiful little boy (who was then too young to understand the magnitude of his father's suffering) are right up at the top.

There's a fair amount of information about Reeve's career as an actor, especially his struggle to reconcile his beloved performance as Superman against his desire to prove himself in other types of roles (which he did in "Street Smart," "Deathtrap" and "Somewhere in Time," even though audiences didn't turn out like they did when he wore the cape and tights). But the filmmakers intersperse this aspect with the account of his accident, survival, and subsequent attempts to manage his pain.

The movie feels a bit rushed or compacted—sometimes, you want it to live inside of a moment for longer than it does. Ilan Eskheri's score, which seems to be aiming for effects comparable to John Williams' "Superman" score, is too ever-present, intrusive, and loud at times; it often seems to be trying to tell us how to feel, unnecessary with a story so inherently inspiring.

But all in all, this is a thoughtful, remarkable piece of nonfiction, working in an accessible commercial vein but doing its best not to take the easy way into any aspect of Reeve's story. It's most impressive when pointing a camera at Reeve's colleagues (including Glenn Close, Jeff Daniels, and Whoopi Goldberg) as they talk about Reeve's attempts to reinvent himself as a visibly paralyzed actor (he did a made-for-TV remake of "Rear Window") and as a director. It's doubly admirable when letting his children tell the story of their father's perseverance and the dedication of Dana Reeve, who is presented as single-mindedly devoted to his physical and emotional care. Documentaries that really know how to listen are increasingly rare, and this is a good one.

The movie deserves a wide audience and, hopefully, will redouble efforts to search for medical solutions that can ease the suffering of people with spinal cord injuries or perhaps one day make them a thing of the past.