One of the perennial dilemmas of movie biographies is that it is easy to film gossip and hard to film art. Thus we get great artists who spend vast quantities of time in bed, leaping up occasionally to dash off a painting, when in real life it was probably more a case of hours spent at work, and then a quick leap into the sack.

Pablo Picasso was one of the more notorious lovers of the century, a man who did not disrespect women so much as value them highly as replaceable possessions. His first love was art, his second love was himself, his third love was what women could do for him. During the decades of his greatness there was no shortage of women eager to see it his way.

In "Surviving Picasso," one of his mistresses, Dora Maar, says, "Without him, there is nothing. After Picasso, only God." And another of his lovers, the faithful Marie-Therese Walter, complains sadly of her poverty while still saving every Thursday and Sunday for his visits. (She is the only person he will trust to cut his hair and nails, and she saves all of the clippings--at his insistence, to be sure, not hers.) "Surviving Picasso" is the story of one lover who was not destroyed by Picasso: Francoise Gilot, who was his mistress from the mid-1940s to the mid-1950s, bore him two children, and walked away in one piece. Played by Natascha McElhone, she is an elegant young woman who projects more confidence than she probably feels the first time she enters Picasso's studio.

He has picked her up in Le Petit Benoit, a little Left Bank bistro, leaving Dora's table to join her, and in his invitation he's left little doubt of his intentions: "Come and see me--but come as if you like me, not because you're visiting the Holy Shrine of Fatima." There is another warning signal as she enters: "You're now in the labyrinth of the Minotaur," he says, "who perishes if he doesn't devour at least two young ladies a day." Why did so many women find Picasso irresistible, even in his old age? Perhaps because he felt himself to be irresistible. And certainly because he was Picasso, who through one period and into another successfully maintained his reputation as the century's greatest artist.

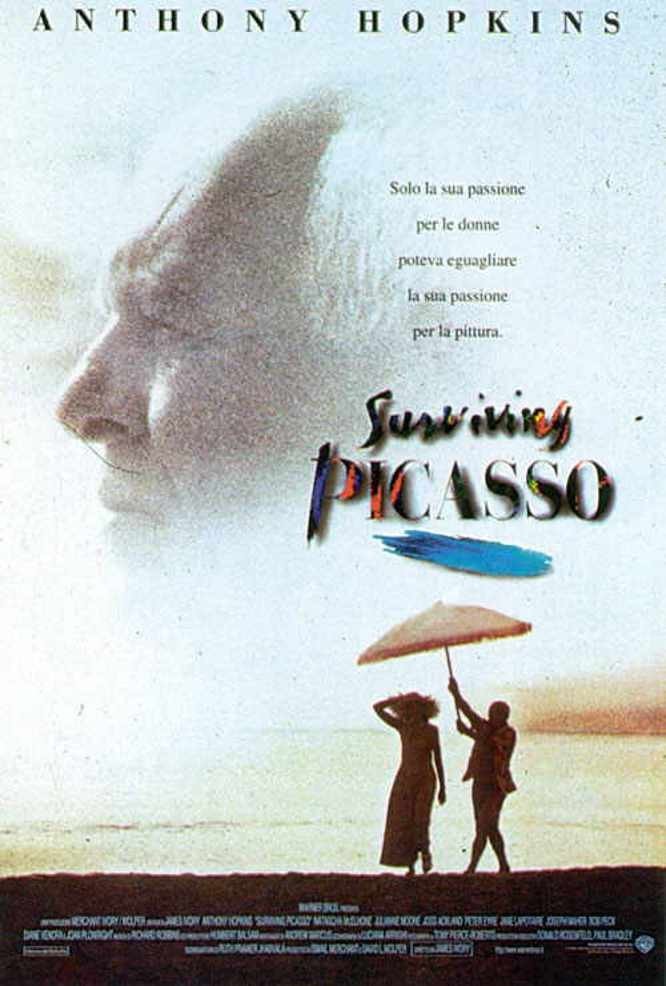

Picasso is played here by Anthony Hopkins, in another great biographical interpretation by an actor of limitless resources. It is less than a year since he convinced me he was Richard Nixon; now he disappears into the idea of Picasso. As Hopkins creates Picasso, he is cruel, abrupt, vain, stingy, a sexual glutton, and yet we can see the dazzling charm and effortless confidence--the certainty of greatness--that inspired new lovers to pursue him, brushing aside all warnings. ("Listen," says Picasso's servant as Gilot falls into the net, "it would be better for you to go home.") The movie is made at one remove from its primary sources. The Merchant-Ivory team was not able to obtain the rights to Gilot's own autobiography, or the permission to show any of Picasso's artwork. So they used another book about Picasso and his lovers ("Picasso: Creator and Destroyer," by Arianna Stassinopoulos), and commissioned fake Picassos. Access to the originals might not have made a difference, since the movie's weakness is its inability to see past Gilot to the great man. "Surviving Picasso" proceeds as if the most important thing in Picasso's life during his time with Francoise was Francoise. (I am reminded of the old story about the actor hired to play a gravedigger in "Hamlet," who describes the play as "about this gravedigger who meets a prince.") We see scenes of seduction, quarrels, and selfishness. We see a faithful chauffeur dismissed after 25 years for a moment of carelessness. We hear the complaints of Picasso's long-suffering assistant, who reveals to Francoise that he is married, lives in a garret, and has to pay for his own train tickets when summoned to join Picasso out of town. This is the backstairs litany of retainers, more interesting in footnotes than as the main story.

Even this limited viewpoint is marred further by two structural problems: The movie breaks down into anecdotes that don't flow or build, and everything is narrated by the Gilot character. McElhone, who is electric and convincing when she's onscreen, is a bad voice-over narrator, and screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala has not helped with language that seems formal and stilted, like a schoolgirl's commentary for an educational film.

There is much to admire in "Surviving Picasso," especially in Hopkins' performance and in the flashes that all of the supporting characters bring. (Joss Ackland has a gentle charm as Henri Matisse, Joan Plowright is self-assured as Francoise's grandmother, and Julianne Moore is edgy and resigned as Dora Maar.) But when it is over we are left with the conclusion that if Picasso had not been a great artist, this story would not have much mattered; as a beast toward women, he was nothing special.