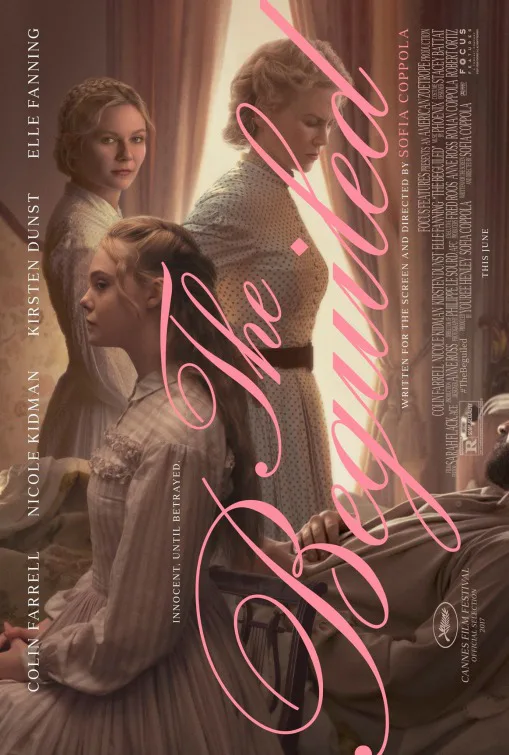

The women stand on the front steps of a dilapidated Southern plantation house, staring out at the muddy road beyond the gate, a road traversed back and forth by battered Confederate troops, heading towards or away from the fluctuating "front." Outside the gates is all restless movement, inside the gates is stasis. Sofia Coppola's "The Beguiled"—a remake (sort of) of the 1971 Don Siegel/Clint Eastwood film—is full of such tableaux. The "meaning" is not explicit in the images, although you could read plenty into it if you wanted to (the women are glimpsed between the iron bars of the gate, isolated from the world of men, etc). With its title-card gigantic in a swirling pink font, like a flourishing header in the diary of a melodramatic teenage girl, "The Beguiled" is a fairy tale, where beautiful spirited women and girls—flawed and filled with contradictory impulses—are locked away from the larger world (some by choice, others because they have nowhere else to go), and how a man disrupts their quiet; how much turbulence a man can bring. Gorgeously shot by Philippe Le Sourd (in his first collaboration with Coppola), "The Beguiled" lingers on its images, allows us time to settle into them.

The film opens with a haunting sequence where a child of 11 (Oona Laurence) gathers mushrooms in a quiet wood. The air is shattered by distant cannon fire. She then discovers the wounded John McBurney (Colin Farrell), a Union soldier who fled his regiment when the battle was at its height, an unmanly act of which he is ashamed. The child decides to take him back to the girls' school where she lives ("Any men about?" McBurney asks her). The school is run by Martha Farnsworth (Nicole Kidman), and there are only 5 students left, as well as the teacher, Edwina (frequent Coppola collaborator Kirsten Dunst). Terrified of "their" soldiers discovering their harboring of an enemy, they lock McBurney up in the downstairs music room, and Martha, with a briskness covering up her fluttery reaction to McBurney's presence, tends to his leg wound, bathing him, the scene unfolding in a series of lovingly erotic shots of Farrell's chest, forearms, calves, neck.

Meanwhile, all through the house, the students—especially the languid Alicia (Elle Fanning), a teenager but already over-ripened, flushed with need and bored out of her mind—huddle by the door, trying to get at least a brief glimpse of the HUNK lying half-clothed on the fainting couch in the dim interior. Coppola really revels in the humor of the situation, treating it affectionately, the students suddenly appearing with pearl earrings in their ears, or dressing up, or sneaking in to give him gifts. Miss Martha looks at all of this in horror and tries to control the situation. But hormones gonna hormone. (Martha is completely male-phobic in the book. Coppola treats it with a lighter touch.)

Thomas Cullinan's 1966 novel (originally titled A Painted Devil) was the basis for the 1971 film, made in the same year as "Dirty Harry." The 1971 film is an entertaining rooster-in-a-henhouse fantasy, wrapped in Southern Gothic histrionics, featuring incest, bed-hopping, amputation, poison, not to mention multiple shots of Eastwood's smooth exposed chest. Director Don Siegel said the film was about "the basic desire of women to castrate men," a pretty clear expression of male anxiety in that particular era. Coppola's adaptation removes quite a bit from the original source material as well as from the earlier film (there's been a lot of controversy about her editing out Matilda, the slave who works at the school, but the absence of the incest sub-plot is even more radical, considering what a large role it plays in the original story.) In the multi-narrator book, Edwina, who forms a special bond with McBurney (the problem is, he forms a special bond with each of them), muses: "Each rumble of the cannons, each swirl of smoke, was a sign of great trouble ... spreading like ripples in a stream to villages and towns and solitary lonely houses all over the land. Perhaps the trouble of the wounded boy would spread and infect people far away from here."

McBurney symbolizes a different thing to each one of them, and he's a shape-shifter, sometimes friendly, or flirty, sometimes polite, sometimes earnest. Farrell, a gifted and fluid actor, is perfect for this role, and it's difficult to imagine another actor pulling it off. You can't manufacture charm like that. Kidman and Durst are both funny and intense, tag-teaming Martha's steel-magnolia energy with Edwina's ladylike delicacy. Fanning, one of the best young actresses working today, is teenage yearning in the flesh, her lazy gestures suggesting restlessness bordering on explosion.

The film suffers a bit from the absence of melodrama (particularly in the case of Martha's backstory), but if you didn't know the original or if you hadn't read the book then that might not matter. This is Coppola's film with Coppola's fingerprint. She is interested in the fleeting, in things not easily said, and here she is interested in the ridiculousness of repressing the sex drive (at one point, Edwina is so turned on she almost collapses against a wall). The film is about that house, the pewter-toned light inside, the way the sunset catches the tops of the columns, the women floating through the overgrown yard, the younger girls lying in the same bed, limbs intertwined, practically a Coppola signature at this point. The interior is the female realm, where women dominate and the male lies in repose, to be gawked at and fussed over. The women are powerful and resourceful ("Edwina, bring me the anatomy book") but ready to tear each other apart to get to that man in the room.

Coppola is not all that interested in explicit commentary or contextualizing larger issues; her interests lie in the peripheral; in what happens when things get quiet; in the way bodies arrange themselves in the frame. You can see it in all of her films. The teenage girl sneaking a peek at V.C. Andrews' "Flowers in the Attic," propped on her slender thighs in "Lick the Star," Coppola's first short film. The five blonde sisters flopped in a pigpile of long limbs and long hair in "The Virgin Suicides." The young woman curled up on the windowsill in her hotel room, her body floating over the cityscape below in "Lost in Translation." The identical strippers in "Somewhere" twirling around poles, their bodies undulating in a surreal and almost serene beauty. The teenage burglar in "The Bling Ring" dabbing her throat with perfume, staring at her reflection in a trance so deep it is disconnected from reality. These moments don't "lead anywhere," but still, they have enormous resonance.

You can't write a thesis statement about what "The Beguiled" is about. It's not that kind of movie. But it's the kind of movie that lingers on in your head, just like the best fairy tales do.