An actress sat next to me at a wedding reception in London, but she used every bit of the plummy diction and faultless projection to reach the cheap seats she learned at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. "You do understand," she intoned as though it was a line from Noel Coward, "that the AC-tor thinks of the crrrritic as the fire hydrant thinks of the DOG." I told her that my most recent review advised audiences to avoid a pop star's new vanity project. "Oh, well," she said, with just a touch of resignation. "If you're going to appeal to my humanity."

Even a critic can't help but be sympathetic to the actor's point of view. They usually go through years of training and rejection and often make themselves very vulnerable to achieve authenticity in their performances, only to be casually tossed aside with a term like "lackluster" or "overblown." That is why we see rather harsh portrayals of critics in film, with actors having a lot of fun turning the tables. There is the acid-tongued and predatory Addison DeWitt, played by George Sanders in "All About Eve," and the merciless restaurant critic tellingly named Anton Ego in "Ratatouille." A key scene in "Citizen Kane" has the eponymous character finishing a scathing review of his wife's singing when the critic, his best friend, gets too drunk to continue. Bob Hope plays a character who reviews his wife's autobiographical play in "Critic's Choice." My favorite fictional critic in a movie is David Niven in "Please Don't Eat the Daisies." He gets caught up in the glittery world of the theater and starts to care more about being witty than being insightful and constructive – until his wife and best friend make sure he learns what he has lost.

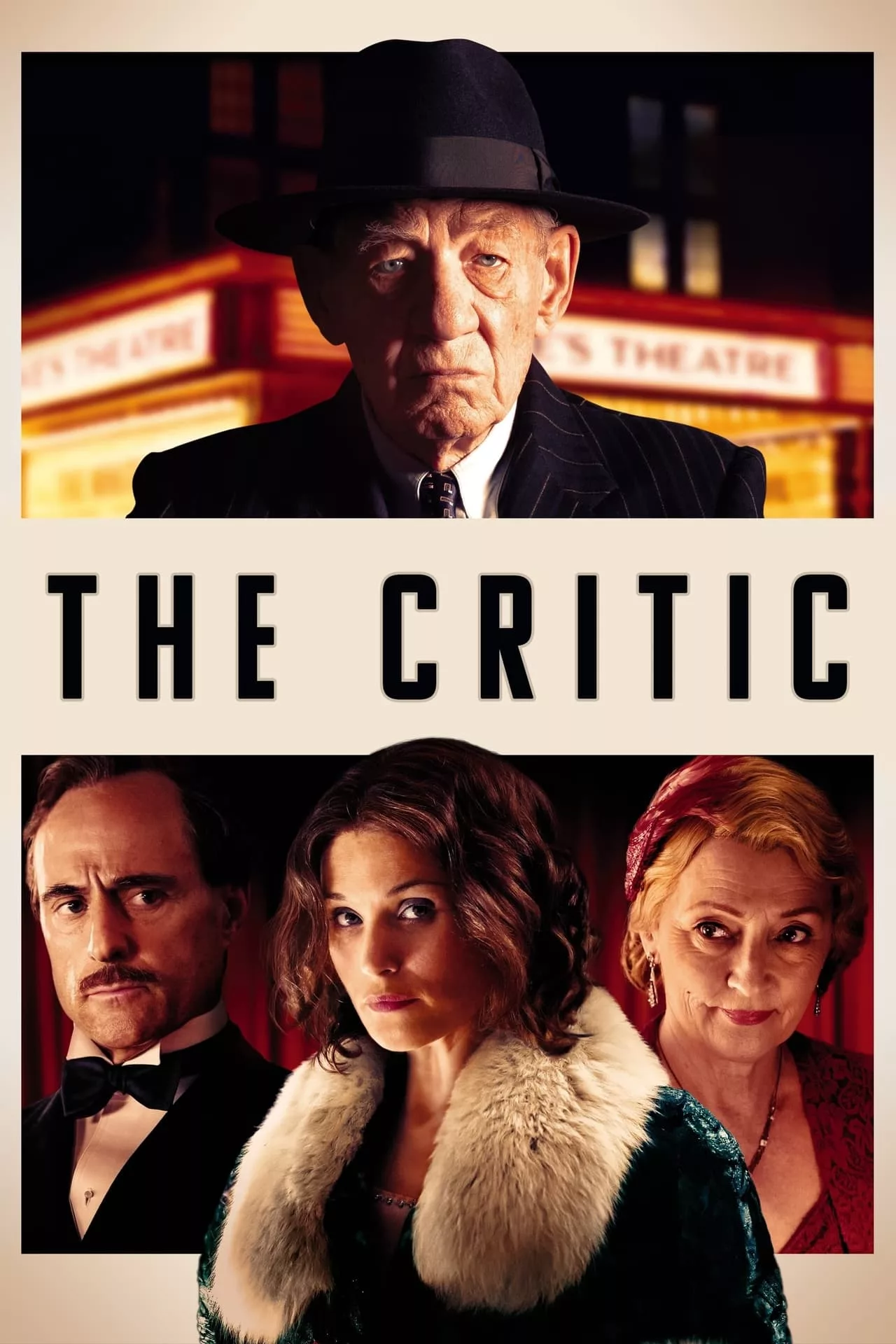

Jimmy Erskine (Ian McKellen), the title character in "The Critic," includes bits of all those critic archetypes. The worst bits. What makes these characters intriguing is the difficulty of maintaining perceptive objectivity without becoming mean. Erskine crossed that line decades ago.

It is 1930s London, and Erskine is a long-time newspaper theater critic, columnist, bon vivant, and busybody. He relishes his power to make or break a performer or a production, and the way his position makes him the center of attention. Seeing plays and writing about them is what he does in between drinking, smoking, feeling superior, and paying young men for "rough trade." He gets a thrill from the "humiliation and danger" as much as the sex. But as the story begins, the newspaper owner who hired him has died, and his son (Mark Strong as Richard Brooke) is making changes.

McKellen is the reason to see "The Critic." This extraordinary actor could not wish for a character better suited to his depth of understanding and experience. Every tilt of his head, every slouch of his shoulders, every angle of his hat, and the astonishing variety of ways he dangles a cigarette from his lip tell us who Erskine is, what matters to him, and how he plans to regain what he considers his rightful status. His interactions with colleagues and friends, his young, Black secretary/lover (Alfred Enoch), and his understatedly contentious discussions with an editor and Brooke are all perfectly pitched. Despite Erskine's very British reserve, McKellen shows him at his most comfortable, his most vulnerable, and his most conniving. Also outstanding (despite thinly conceived characters) are Gemma Arterton as Nina Land, an anxious actress desperate for a good review, and Lesley Manville as her mother.

The other element that pulls us into the film is the world-building by production designer Lucienne Suren. Every space in the film, particularly the homes of Erskine, Brooke, and Brooke's daughter Cora (Romola Garai) and her Jewish husband Stephen (Ben Barnes), a portrait painter, plus the newspaper office and a restaurant frequented by the characters are gorgeously imagined, luxurious, elegant, and classic. They are filled with solid older pieces carefully maintained and beautifully lit, with just a few modernist touches to reflect recognition of 20th-century design and a shift that will soon transform every element of English life. This is England between the two World Wars, still grounded in the past but with glimpses of what lies ahead with a reference to a fascist politician and a run-in with racist Blackshirt thugs. In the first half of the film, the conflicts between Brooke and Erskine parallel these early, almost unconscious indicators of the upheavals ahead, setting us up for a thoughtful exploration of the way a critic's insistence on objectivity can make him miss what really matters.

Instead, the movie goes off the rails, from an intriguing set-up to a contrived storyline that would have had Erskine rolling his eyes. Despite Brooke's warning that any public embarrassment will be cause for firing, Erskine continues to take risks with the young men in the park. When he's arrested, Brooke is happy to get rid of him. Erskine will do anything to get his job back, and he thinks he can use the vulnerable Nina Land to help him. The ensuing plot depends on the weakest of premises, the idea that even in a big city, the characters all happen to be connected in an overly convenient closed circle. From that point on, the film mires itself in melodrama that mistakes increasingly dire consequences for increasing interest. Instead, they take us further from the intriguing first half until the terms "lackluster" and "overblown" seem to apply.