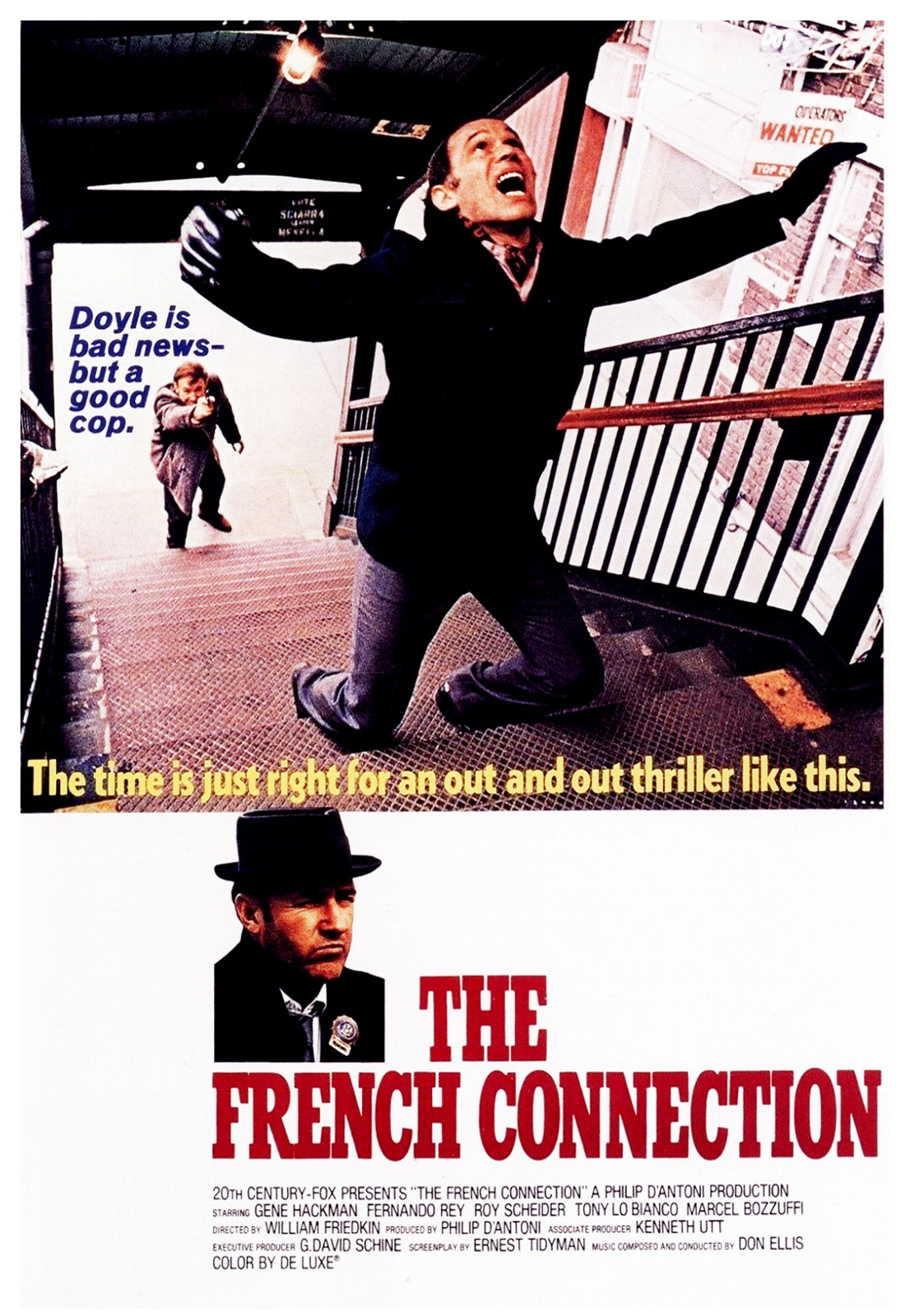

"The French Connection" is routinely included, along with "Bullitt," "Diva" and "Raiders of the Lost Ark," on the short list of movies with the greatest chase scenes of all time. What is not always remembered is what a good movie it is apart from the chase scene. It featured a great early Gene Hackman performance that won an Academy Award, and it also won Oscars for best picture, direction, screenplay and editing.

The movie is all surface, movement, violence and suspense. Only one of the characters really emerges into three dimensions: Popeye Doyle Gene Hackman, a New York narc who is vicious, obsessed and a little mad. The other characters don't emerge because there's no time for them to emerge. Things are happening too fast.

The story line hardly matters. It involves a $32 million shipment of high-grade heroin smuggled from Marseilles to New York hidden in a Lincoln Continental. A complicated deal is set up between the French people, an American money man and the Mafia. Doyle, a tough cop with a shaky reputation who busts a lot of street junkies, needs a big win to keep his career together. He stumbles on the heroin deal and pursues it with a single-minded ferocity that is frankly amoral. He isn't after the smugglers because they're breaking the law; he's after them because his job consumes him.

Director William Friedkin constructed "The French Connection" so surely that it left audiences stunned. And I don't mean that as a reviewer's cliché: It is literally true. In a sense, the whole movie is a chase. It opens with a shot of a French detective keeping the Continental under surveillance, and from then on the smugglers and the law officers are endlessly circling and sniffing each other. It's just that the chase speeds up sometimes, as in the celebrated car-train sequence.

In "Bullitt," two cars and two drivers were matched against each other at fairly equal odds. In Friedkin's chase, the cop has to weave through city traffic at 70 m.p.h. to keep up with a train that has a clear track: The odds are off-balance. And when the train's motorman dies and the train is without a driver, the chase gets even spookier: A man is matched against a machine that cannot understand risk or fear. This makes the chase psychologically more scary, in addition to everything it has going for it visually.

The movie was shot during a cold and gray New York winter, and it has a doomed, gritty look. The landscape is a waste land, and the characters are hardly alive. They move out of habit and compulsion, long after ordinary human feelings have lost the power to move them. Doyle himself is a bad cop, by ordinary standards; he harasses and brutalizes people, he is a racist, he endangers innocent people during the chase scene (which is a high-speed ego trip). But he survives. He wins, too, but that hardly matters. "The French Connection" is as amoral as its hero, as violent, as obsessed and as frightening.

The key to the chase is that it occurs in an ordinary time and place. No rules are suspended; Popeye's car is racing down streets where ordinary traffic and pedestrians can be found, and his desperation is such that we believe, at times, he is capable of running down bystanders just to win the contest. I had an opportunity at the Hawaii Film Festival in 1992 to analyze the sequence a shot at a time, using a stop-action laserdisc approach, at a seminar honoring the work of the cinematographer, Owen Roizman. He recalled the way the whole chase was painstakingly story-boarded and then broken down into shots that were possible and safe, even though actual locations were being employed. Lenses were chosen to play with distance, so that the car sometimes seemed closer to hazards than it was. But essentially, the chase looked real because its many different parts were real: A car threads through city streets, chasing an elevated train.

The other key element in the film, of course, is Hackman. He was already well known in 1971, after performances in such films as "Bonnie and Clyde," "Downhill Racer" and "I Never Sang for My Father." But it's probably "The French Connection" that launched his long career as a leading character sta r-- a man with the unique ability to make almost any dialogue plausible. As Popeye Doyle, he generated an almost frightening single-mindedness, a cold determination to win at all costs, which elevated the stakes in the story from a simple police cat-and-mouse chase into the acting-out of Popeye's pathology. The chase scene has, in a way, been a mixed blessing, distracting from the film's other qualities.