The inspirational sports drama "The Hill," about the poor and disabled son of a preacher who becomes a professional baseball player, feels longer than it is because the characterizations and story don't rise to meet the acting and filmmaking and because almost everyone in the movie (save for a bully and his cronies, briefly glimpsed in two scenes) is so earnest and well-meaning. It's the equivalent of a church service by a pastor who's good at his job but lacks the spark that makes people say amen without prompting.

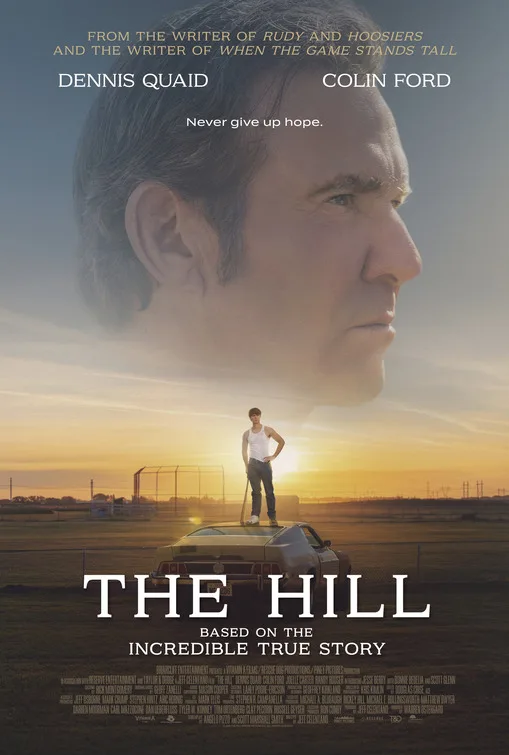

Directed by Jeff Celentano from a script by the late Scott Marshall Smith ("Men of Honor") and Angelo Pizzo (who wrote the classics "Rudy" and "Hoosiers"), "The Hill" retells the true story of Fort Worth, Texas native Rickey Marshall. Like Pizzo's signature screenplays, this tale is in the spirit of the original "Rocky," where the hero's achievements are far more modest than the Hollywood usual but stirring (arguably more so) because the stakes are small and the obstacles relatable. Hill, a Baptist preacher's son, grew up fantasizing about playing Major League baseball despite a degenerative spinal disease that forced him into leg braces. He also grew up so poor that his family couldn't afford proper equipment: he taught himself to hit using sticks and stones, with his older brother pitching and coaching. Despite all this, Hill developed into a power hitter, played three months for the Montreal Expos at 19, and made it through four seasons in the minor leagues.

The problem isn't that this is a faith-based film aimed at a specific market niche (some of the greatest films ever made focus on spirituality). It's the project's bland vision. Even legitimate, painful conflicts between characters with equally valid but irreconcilable agendas (such as the hero, who is torn between what he believes to be two destinies, playing ball and following in his preacher dad's footsteps) feel programmed even though they're drawn from life. It doesn't help that the hero and a few other major characters (including his love interest) have two-and-a-half dimensions at best and are so altogether pleasant, even when distressed or angry, that it's hard to see how anyone could have rational (or even irrational) objections to anything they do, say, or want.

Jesse Berry (of "9-1-1: Lone Star") plays Rickey as a boy, and Colin Ford ("Under the Dome") steps in to play the teenage version. The film's minimal edge comes from Rickey's relationship with his dad, James (Dennis Quaid). James believes his son's destiny is to succeed him behind the pulpit, opposes his baseball dreams, and even likens his secret baseball card collection to a gallery of false idols. This is reminiscent of both versions of "The Jazz Singer," the story of a young man who would rather be a secular musical performer than a cantor, except that in this case, the hero loves preaching the word and is great at it. ("I thought I was going to be the best Baptist preacher," Hill told Risen magazine. "I was going to be the next Billy Graham.")

Whenever "The Hill" lets Rickey and James verbally spar about faith and sports, the movie transcends cliche. The screenplay lets opposing forces gently push against each other without resolution. You get a clear sense of how people's conditioning and pathologies impede them from making the right choice. Young Rickey eloquently explains to his father that he can be God's representative on the field as effectively as he can in a church and that the two callings are not in opposition, then gives him a drawing of a baseball diamond in which opposing bases have been connected with straight lines to create a cross shape. You'd think such a display of creative imagination and sincerity would persuade the boy's father to change his mind and support him, but no. He lets Rickey play ball, but six years later, when Rickey is a high school star, he tells visitors to the family's home that he has yet to attend a game. (No bets will be taken on whether Dad eventually shows up in the stands.)

When it's not wrestling (however nicely) with spiritual matters, "The Hill" is a well-meaning but dutiful trudge toward an ordained destination. Nearly every scene extends the expected beats and moments for no apparent reason (this isn't Slow Cinema; it's just slow). Despite building nearly every scene around him, it never gives us any sense of Rickey's emotional interior. He's just a polite, talented kid who wants to do a thing but is restrained from doing it by people who mean well. The central relationship's potential is blunted, too. Except in the verbal duets between father and son, James is an emotionally constipated scold who is established as having a good heart beneath it all. The movie allows him to be stubborn and unreasonable, but it doesn't have the nerve to let him cross over into monstrousness or even sustained dislikability. There's a scene where James takes Rickey's older brother Robert (Mason Gillett) behind the house to whip him with a belt as punishment for supporting Rickey's baseball dreams, but during the windup, he chokes back tears and sends him inside unscathed. Brutal physical punishment still happens in American homes, including ones where families attend church together and contemplate the life and teachings of Jesus. But this is not the kind of movie that will show the contradiction and complexity of that life by having a movie star beat a child.

Most of the characters are a notch or two above "types." Ricky's girlfriend Grace (played by Siena Bjornerud as a teen and Mila Harris as a child) is confident and mature throughout, tossing out snappy patter that suggests that somebody ran the Annie Savoy character from "Bull Durham" through a "Gilmore Girls" filter. Scott Glenn shows up late in the movie as the baseball scout who lets Rickey strut his stuff (a 40-years-later "Right Stuff" reunion for him and Quaid) and manages to convince us that the character had a full and fascinating life before he stepped into the frame. But that's the sort of alchemy that has more to do with the depth of an actor's skills and experience than the story he's helping tell.

Joelle Carter, so fiery on "Justified," gets one sustained, powerful scene as James' wife Helen, who would like to oppose him but can't summon the strength, but she's otherwise sidelined and sometimes reduced to watching the other characters as if they're on TV. Bonnie Bedelia, who would be a name-above-the-title movie star in a just world, fares slightly better as the hero's salt-of-the-earth grandmother, rocking a silver Ma-Joad-goes-to-the-Oscars hairstyle. (Another issue worth getting into somewhere besides this piece: age-wise, the casting in "The Hill" is retro in a bad way. Carter is almost 20 years younger than Quaid, and Bedelia is only eight years older.)

According to Rickey Hill's website and pre-release interviews, he now follows in his father's footsteps by spreading the Good Word while also selling hemp-based wellness kits. Some people believe that a brief taste of success can be more debilitating for a person than never tasting it at all. Hill doesn't feel that way. He also doesn't act as if he was robbed of anything greater than what he got, either by his physical limitations or his upbringing, even though many people who've had that sort of experience might feel that way. A documentary about his whole life journey would likely be more compelling than this recreation of his early years. It would have a better shot at depicting Hill and every other important player in his story as a three-dimensional human being. And it might speak to the realities of most people's lives, which rarely have the perfect dramatic shape (complete with a happy ending) that Hollywood prefers.

Now playing in theaters.