In 2004, two years before the St. Andrews Agreement, I visited a friend in Belfast. Changes were already apparent, if you knew what to look for. A Starbucks had opened, an encouraging sign that corporations were no longer shying away from a war zone. There were still echoes everywhere of the decades-long strife that had shattered the community. I took a "black cab tour," and the guide pointed out a pub where a bomb had gone off in the past, adding, almost casually, "My girlfriend's Da got his leg blown off there." It was such a clear example of the multi-generational aspect to The Troubles, to any civil war really, how grief and loss are passed down.

When Martin McGuinness died this past March, the tone of the obituaries spoke to the complexity of his legacy. The headlines were mostly variations of: "From IRA Terrorist/Commander to Peacemaker." Or "From Sinn Féin Leader to First Deputy Minister." The comments sections seethed with arguments. This was a man who started out as a kid throwing rocks at British soldiers, who ended up shaking hands with Queen Elizabeth, a surreal moment if ever there was one, as well as sharing political power with long-time rabblerouser Reverend Ian Paisley (the man who heckled Pope John Paul II in 1988 with the immortal words: "I denounce you, Anti-Christ!"). Paisley and McGuinness actually did become if not friends then allies in their roles as First Minister and deputy First Minister of the new power-sharing government, post the 2006 St. Andrews Agreement.

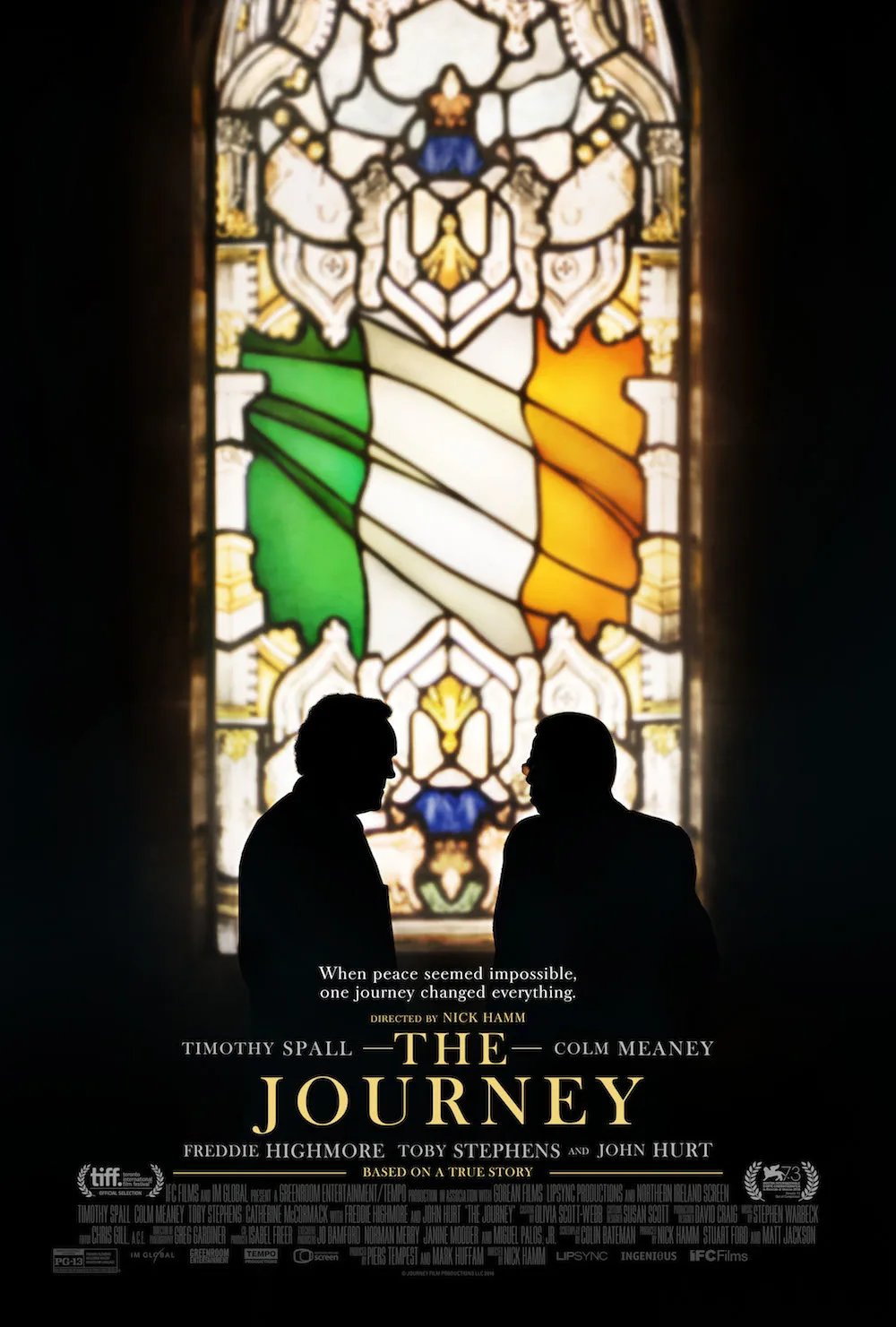

"The Journey," directed by Nick Hamm, written by Colin Bateman, announces at the outset, "This story imagines that journey" ("that journey" being how Paisley and McGuinness decided to bury the hatchet). It's a weird sentence and I got tripped up on it initially. Since the film is filled with real-life people (Gerry Adams, Tony Blair, Bertie Ahern, etc.), and since it takes place at a real-life event (the St. Andrews peace talks), veering off into a pretend-universe where Paisley and McGuinness are trapped together via circumstances beyond their control and HAVE to get along ... is a simplified grade-school version of political realities. It's "The Odd Couple" with Irish accents. There's a naivete at work in the concept: If only these men could bond about football, their wives, their kids ... if only these staunch enemies could see one another as people, then maybe the Catholics and Protestants will join hands in love and harmony!

Did Ian Paisley (Timothy Spall) and Martin McGuinness (Colm Meaney), as the film shows, go on a bizarre little road trip where they were forced to listen, grow, change? Of course not. Unfortunately for the film, the real-life version of how these two mortal enemies became so close that they were referred to in the press as "The Chuckle Brothers" is way more interesting than the "imagined" version presented in the film.

According to the film's imagined universe, in the middle of the peace talks, Ian Paisley had to fly back to Belfast for his Golden Anniversary wedding celebration. Martin McGuinness insists on accompanying Paisley. Tony Blair (Toby Stephens) and M15 chief Harry Patterson (the late John Hurt) are thrown into a panic. McGuinness and Paisley MUST have their emotional "breakthrough" during their hour-long car ride to the airport, otherwise there will never be peace in Northern Ireland. Their solution to this is to deck the car with hidden cameras, and provide the fake chauffeur with a Bluetooth (through which they whisper suggestions to get the two scowling adversaries talking). Patterson, Blair, and a taciturn Gerry Adams (Ian Beattie) watch the entire thing unfold over video monitors from a command post at St. Andrews, as though it's Mission Control in Houston.

Paisley sits in outraged silence for the first portion of the drive, while McGuinness tries to make conversation. Then a series of phony events—a detour through a forest, a run-in with a deer, a confrontation at a gas station—transforms the two men, and they finally start talking. McGuinness and Paisley argue over familiar territory: Bloody Sunday, the Enniskillen bombing, the hunger strike. Their views are so diametrically opposed that they basically live in alternate realities. They have fights, which include cliched lines like: "You are so defensive!" "Alright, walk away, walk away, that's what you do!" The moments where McGuinness gets the icily reserved Paisley to crack a smile are sitcom-phony, at best, and it's made even more egregious by Tony Blair and Gerry Adams gasping with excitement from afar that the Emotional Healing has begun.

In 2016, Spall played, back-to-back, two inflammatory and despised real-life men, Holocaust denier David Irving in "Denial" and now Paisley. Spall did so, in both cases, without pleading for any sympathy for the characters, suggesting the striations of fragility, narrowness, and rigidity in these men's emotional makeup. In "Denial," he is vigorous, staunchly upright. In "The Journey" he is believably decrepit and frail. His hatred of the man in the car with him—and all that that man represents—is so believable that it makes his rock-hard refusal to open up to McGuinness' joking comments understandable. His voice is a dead ringer for Paisley's booming religious-harangue tones. (After the doomed Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985, Paisley addressed a crowd of protesters in Belfast, screaming, famously, "Margaret Thatcher tells us that that [the Irish] Republic should have some say in our province. We say NEVER! NEVER! NEVER! NEVER." Paisley's gigantic voice thunders "Never" over and over again in a kind of incantatory rhetoric, and Spall does not shy away from the intimidating size of Paisley's voice.) Meaney has a thankless role, the McGuinness of "The Journey" being the guy who has to persist in warming up Paisley, almost like a Life Coach, using his charm and humor.

The final exchange between Paisley and McGuinness, when they shake hands, is the best, but by then it's far too late. The plot-manipulations and artificial events stage-managed by Mission Control back in St. Andrews all serve to diminish the peace talks, the importance of tough compromise, and the reality of what is actually required of politicians when they decide to sit down at a table such as that one.