The first and last shots of "The War of the Roses" show us a divorce attorney with a tragic tale to tell. He informs a client that there will be no charge. "I get paid $450 an hour to talk to people," he says, "and so when I offer to tell you something for free, I advise you to listen carefully." He wants to tell the story of a couple of clients of his, Oliver and Barbara Rose, who were happy, and then got involved in a divorce, and were never happy again.

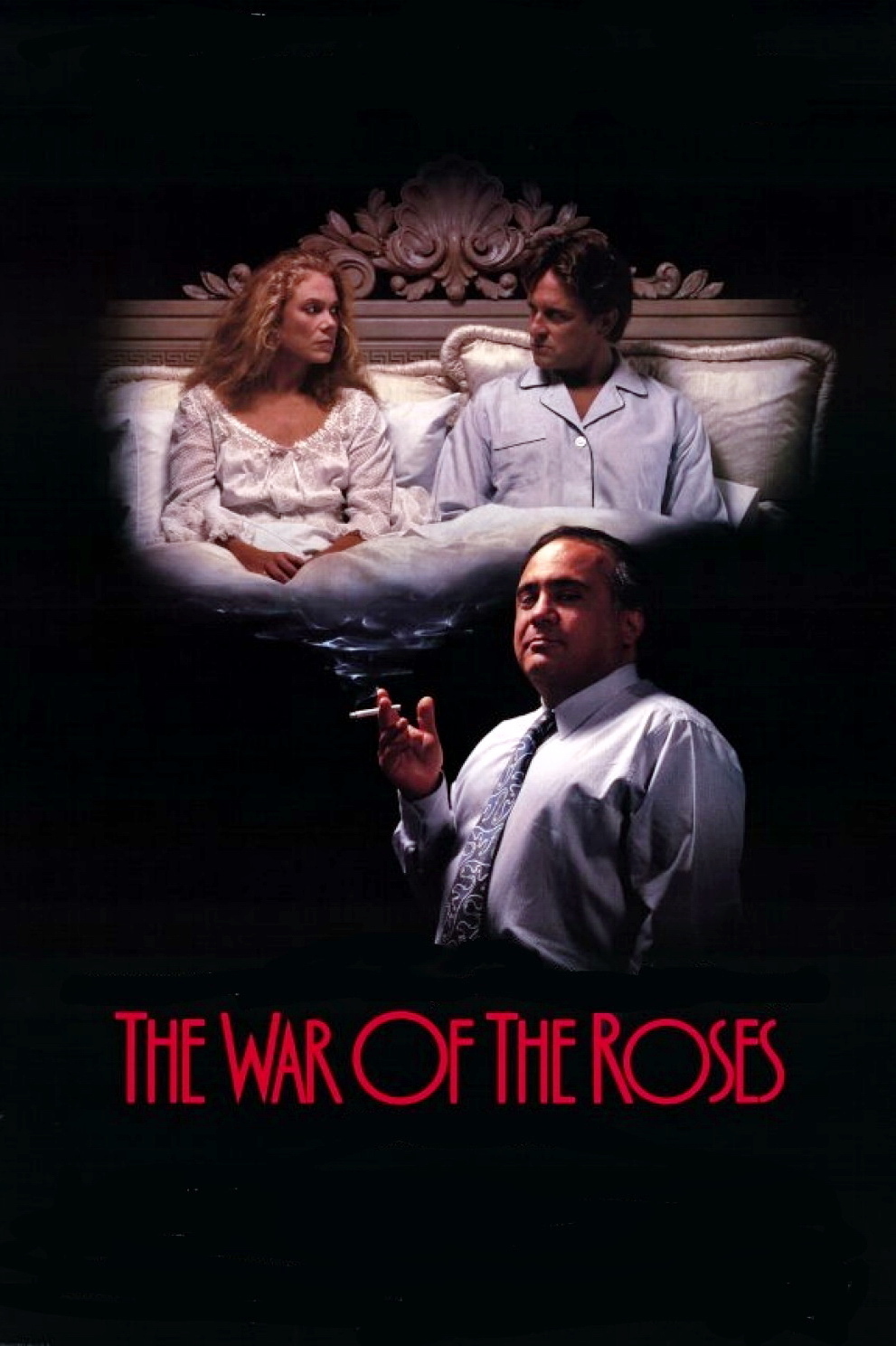

The attorney is played by Danny DeVito, who also directed "The War of the Roses," and although I usually dislike devices in which a narrator thinks back over the progress of a long, cautionary tale, this time I think it works. It works because we must never be allowed to believe, even for a moment, that Oliver and Barbara are going to get away with their happiness. The lawyer's lesson is that happiness has nothing to do with it, anyway. He doubts that any marriage is destined to be happy (of course, as a divorce lawyer, he has a particular slant on the subject). His lesson is more brutal: "Divorce is survivable." If only the Roses had listened.

The movie stars Michael Douglas and Kathleen Turner as the doomed Roses, and although both actors also teamed with DeVito in "Romancing the Stone," no two movies could be more dissimilar. "The War of the Roses" is a black, angry, bitter, unrelenting comedy, a war between the sexes that makes James Thurber's work on the same subject look almost resigned by comparison.

And yet the Roses fell so naturally and easily into love, in those first sunny days so long ago. They met at an auction, bidding on the same cheap figurine, and by evening they were in each other's arms ("If this relationship lasts," Barbara muses, "this will have been the most romantic moment of my life. It is doesn't, I'm a complete slut.") He went into law. She went into housekeeping. They were both great at their work. Oliver made a lot of money, and Barbara spent a lot of money, buying, furnishing and decorating a house that looks like just about the best home money can buy. Meanwhile, a couple of children, one of each sex, grow up and leave home, and then Barbara decides she wants something more in life than the curatorship of her own domestic museum. One day she sells a pound of her famous liver pate to a friend and realizes that she holds in her hand the first money she has actually earned for herself in 17 years. It feels good. She asks for a divorce. She wants to keep the house.

That is the beginning of the war. There have been battles of the sexes before in the movies - between Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn, between George C. Scott and Faye Dunaway, between Mickey and Minnie - but never one this vicious. I wonder if the movie doesn't go over the top. The war between the Roses begins in the lawyer's office and escalates into a violent, bloody conflict that finally finds them both barricaded inside their house beautiful, doing battle with the very symbols of their marriage: the figurines, the gourmet kitchen range, the chandelier.

There are a great many funny moments in "The War of the Roses," including one in which Turner (playing an ex-gymnast) springs to her feet from a prone position on her lawyer's floor in one lithe movement and another in which Douglas makes absolutely certain that the fish Turner is serving some of her clients for dinner will have that fishy smell. But the movie treads a dangerous line. There are times when its ferocity threatens to break through the boundaries of comedy - to become so unremitting we find we cannot laugh.

It's to the credit of DeVito and his co-stars they they were willing to go that far, but maybe it shows more courage than wisdom.

This is an odd, strange movie and the only one I can remember in which the moral is, "Rather than see a divorce lawyer, be generous - generous to the point of night sweats."