"In every generation the Irish people have asserted their right to national freedom and sovereignty; six times during the past 300 years, they have asserted it in arms." -- Proclamation of the Irish Republic (1916)

It begins in the chaos of combat, men and boys wielding their weapons on the battlefield, shouting and cursing and fighting. Sure, it's only an amateur hurling match, an Irish game similar to field hockey, and the weapons are bladed wooden sticks.

But this is Ireland in 1920 and there's a war going on -- a guerrilla war for the independence of the Irish Republic, pitting the freedom fighters against the British army, the impoverished Irish workers against the English land barons, and eventually brother against brother.

These lads are about to be sucked into the middle of it, for even their game of hurling is a violation of the English government's ban against public meetings by Irish citizens. Only minutes after the match, one of their number, a 17-year-old boy, will be assaulted by the brutal "Black and Tans" (primarily demobilized British soldiers from World War I) for the crime of refusing to give his own name in English.

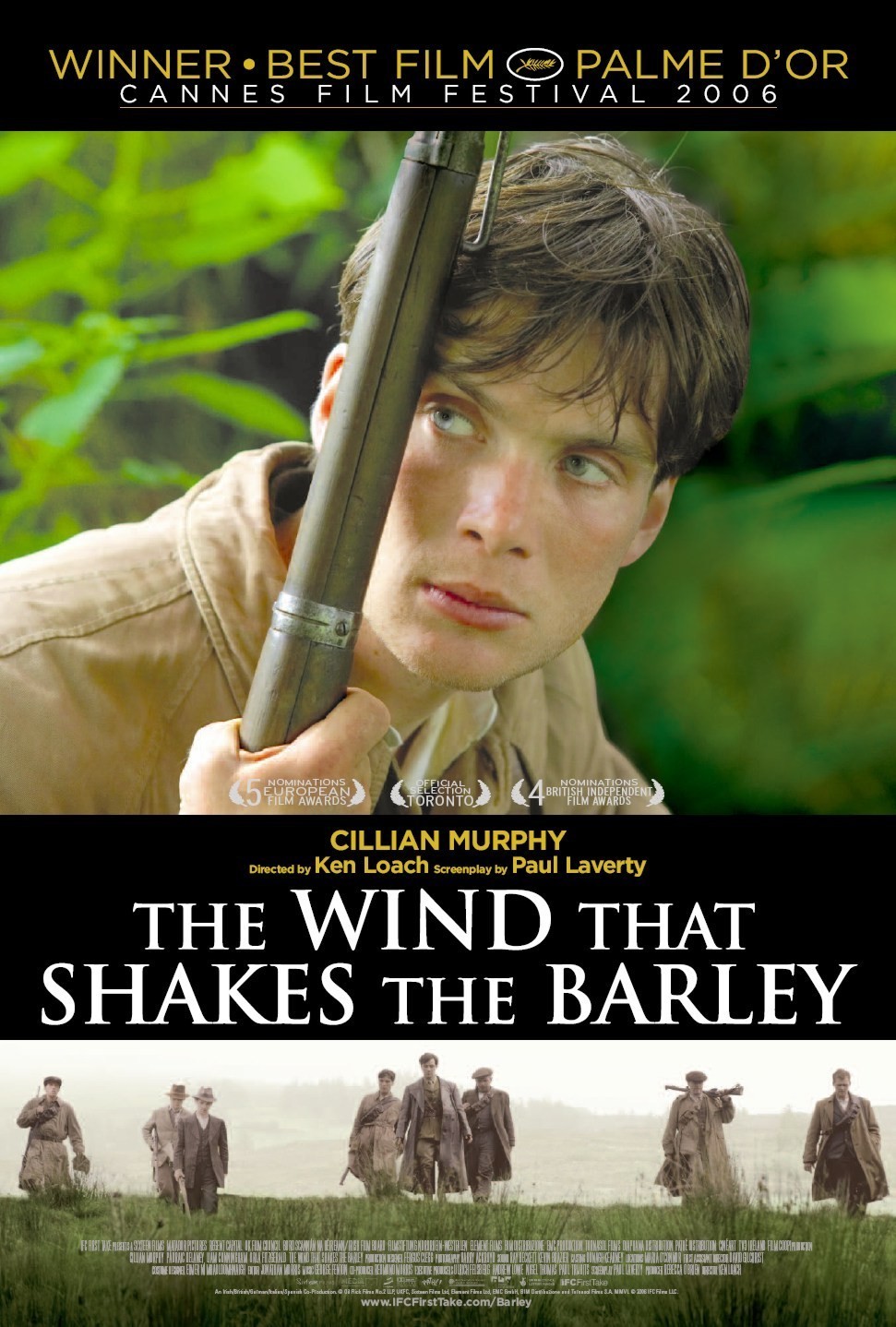

You don't have to know about the history of "the troubles" in Northern Ireland to be swept up in the human drama of Ken Loach's "The Wind That Shakes the Barley," which won the Palme d'Or at the 2006 Cannes Film Festival.

With almost tactile immediacy -- you almost can smell the smoke and the wild grasses in the hills, feel the rain and the fog in your bones -- this movie places you shoulder to shoulder with people who are living and dying for their country, their families, their friends and their principles.

As a so-called period film, "The Wind That Shakes the Barley" feels breathtakingly authentic, but never "old." Cinematographer Barry Ackroyd captures the past with fresh painterly detail, in muted blues, grays, browns and greens, and some lamp-lit interiors invoke the palette of van Gogh's "The Potato Eaters." But while this may be a historical piece, it's history told in the vivid present tense. You feel like you're right there, in the wind-swept hills training with the IRA, or in a public meeting room where partisans passionately argue international politics and personal morality in plain-spoken, sometimes halting language that occasionally rises to heartrending eloquence.

We've seen some fine war movies recently -- and not all of them contemporary documentaries -- from Clint Eastwood's "Flags of our Fathers" and "Letters from Iwo Jima" to Rachid Bouchareb's "Days of Glory" ("Indigenes"). "The Wind That Shakes the Barley" ranks with the best of them -- and and among the best war films ever made. There are echoes of Stanley Kubrick's "Paths of Glory," set in France just a few years earlier, and Loach's film is worthy of that comparison -- but it's told from down at the grassroots level.

The title of the film comes from the lines of a song about the Irish Rebellion of 1798, penned by Robert Dwyer Joyce (1830-1883), about a young man who sacrifices a normal life with his true love to join the cause of the "bold, united men":

'Twas hard the woeful words to frame to break the ties that bound us / But harder still to bear the shame of foreign chains around us.

In the song, as in the film, a single decision -- or a single bullet -- can change the destiny of an individual, a family, a community or (after generations of repercussions) even a nation. Damien O'Donovan (played by the superb actor Cillian Murphy, from "Batman Begins" and "28 Days Later") is a medical student at University College Cork who's about to go off to train as a doctor at a London hospital. Both he and his brother Teddy (Padraic Delaney), a former seminary student, are active in the Irish Republican Army, fighting for the legitimacy of the Sinn Fein party's sweeping victory in the 1918 election, and for permanent Irish independence.

But the British are using strong-arm tactics to maintain their empire -- not only in Ireland, but in India, Iraq, Palestine, African colonies, and elsewhere.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 (negotiated in part by legendary Sinn Fein leader and Irish nationalist Michael Collins) proposes an Irish Free State within the British Commonwealth, while Unionist Northern Ireland would remain within the United Kingdom. The debate over the treaty further divides the Republicans, with Damien rejecting it as a sellout, and Teddy favoring it as an incremental compromise. As Damien says later, "I tried not to get into this war, and did. I now try to get out, and can't."

History inevitably repeats itself, and two films that are most illuminating about the occupation and insurgency in Iraq are about the centuries-old conflict in Ireland: "The Wind That Shakes the Barley" and "Bloody Sunday," set 50 years after "Barley," by director Paul Greengrass ("United 93"), who takes more of a documentary-like, but no less immersive, approach to dramatizing the 1972 massacre of Irish protesters by the British army. The events of that one terrible day fueled the IRA's guerrilla warfare for generations to come.