How to describe the art of Touko Valio Laaksonen, aka Tom of Finland? Shall I compare thee to a Village People wet dream? No, that's not quite it. His depictions of gay masculinity, to my eye, are kind of a gender inversion of the iconography of, say, a female bombshell like Jayne Mansfield. The men who sprang from the imagination of Tom of Finland are perfectly chiseled, bubble-butted, well-endowed boys who can't help it. Their emotional range runs the gamut from friendly (there are some big smiles) to intimidating (there are more impassive-to-frownlike expressions, often camouflaged by thick mustaches). Heterosexual males had their Vargas pinups and other varieties of cheesecake. Tom of Finland drew their gay equivalents, but in a way that tended more toward the surreal/irrational, at least to my eye. A part of the effect had to do with the fact that so much of his artwork was done in black-and-white, pencil drawings of such exquisite and varied shading that one could marvel at the peculiar, painstaking craft as much as one might drool over the impossible physiques.

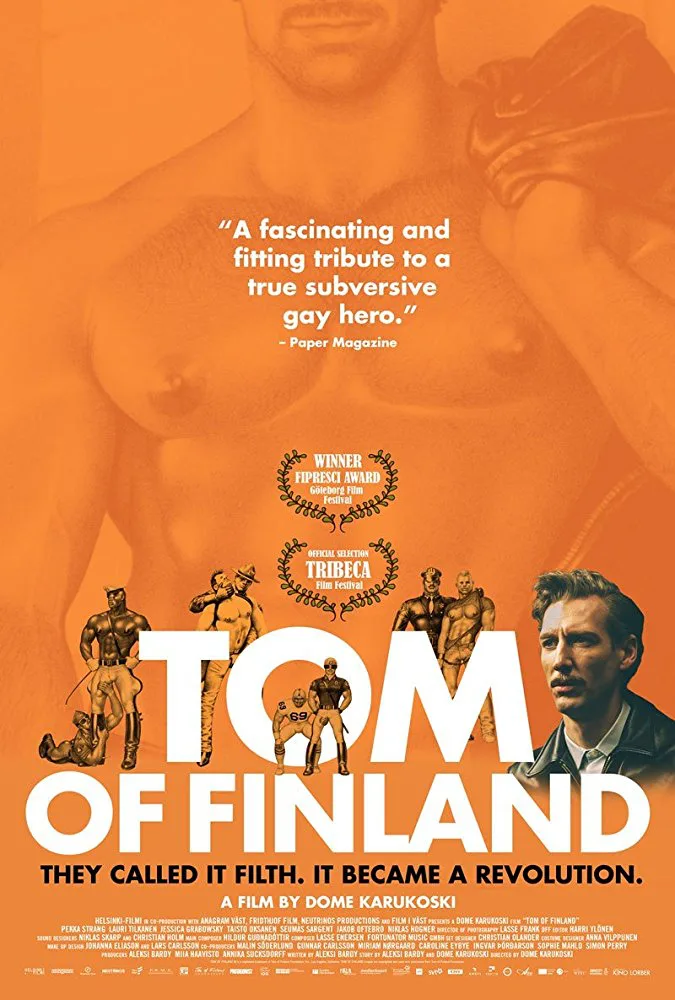

Laaksonen lived from 1920 until 1991, and while he moved comfortably and, if this film is to be believed, delightedly in international gay circles, he was not known as a personality in the mainstream culture. This fiction film, directed by Dome Karukoski and written by Aleksi Bardy (in collaboration with, apparently, five other scenarists/contributors), is a heartfelt tribute to the artist. It's also a too-often diffuse one.

The movie opens with Pekka Strang, who plays the title character, in rather unconvincing old-age makeup sitting in what looks like a railway station waiting room, having a conversation in English. The framing device is a celebration he is given in America—which was a country where his work could be more openly celebrated than his native land, where homosexuality was a crime until 1971, and its "promotion" was a crime until 1999, several years after Laaksonen's death. The movie flashes back to World War II, in which Laaksonen was a soldier; a defining event of his time in the army, the movie tells us, was when he stabbed to death a Russian parachutist. Shorter shrift is given to the Nazis, of whom the real-life Laaksonen once observed, "they have the best uniforms." A different film might have made dramatic hay out of an examination of Laaksonen's abhorrence of what the Nazis' stood for versus his admiration for a certain strain of fascist fashion/style, but this is not a movie with a lot on its mind.

Rather, it's all about personal struggle. "Tom" hides his drawings from his sister, who disapproves of his preferences, referring to them as a "phase." There's a bit of drama when a roomer arrives, and a possible romance between him and the sister turns into a lifelong love story for "Tom." There is not a lot concerning the job Laaksonen had at the Finnish office of McCann Erickson, the advertising giant. The most interesting stuff in the movie is about the artwork—not how Laaksonen made it, the movie is hardly concerned with craft, but rather its initial uses. How Laaksonen first used his postcard size-drawings as invitation cards of a sort, requests to men he found attractive as to whether they were interested in that sort of thing. In a society that makes homosexuality illegal, gays are obliged to speak in code, and that the drawings served as an extension of code—as a crossing of little or no return in certain respects—is fascinating.

When "Tom" starts selling his drawings in America and begins to travel there, the movie takes on an almost magical-realist tone. In the ‘50s and ‘60s "Tom" has to live in shadows, and a trip to Berlin during which authorities discover one of his drawings is a near-catastrophe for him. In Beverly Hills, when a group of cops walks in on a pool party his hosts have arranged for him, Laaksonen fears the worst, but the scene ends with an amusingly ironic twist. Unfortunately, little else in the movie carries that kind of impact. Its lively finale is heartening, given the patience that Laaksonen was obliged to exercise before he could live his life out in the open. But the insights of the movie are too scant for much of a real impression to take hold of the viewer.