"I Can't Let You Throw Yourself Away," sings Randy Newman, Pixar's bard, in a montage from "Toy Story 4." The song's title is aimed at Woody (Tom Hanks), a friend to his original owner, Andy, and later to Bonnie, a five-year old who inherited Andy's toys at the end of "Toy Story 3" and is shown refining her own playtime rituals that don't always include Woody. Secondarily, the song is officially aimed at a new character, Forky (Tony Hale), a plastic spork with popsicle-stick feet and pipe cleaner arms, created by Bonnie with material supplied by Woody during orientation day at kindergarten. Typical of "Toy Story," a series where inanimate objects don't merely have personalities but existential crises, Forky keeps breaking away from Bonnie and Woody and trying to hurl himself into the nearest trash receptacle. This is not a comment on his own feelings of worthiness. but an expression of the fact that Forky is, after all, a utensil, and feels most comfortable in the trash, secure in the knowledge that he fulfilled his purpose.

But "I Can't Let You Throw Yourself Away" also expresses the audience's feelings for this beloved series, which has continued over nearly a quarter century, producing four installments that run the gamut from excellent to perfect. We don't want the story of "Toy Story" to end, but we also don't want it to become a plaything taken down from the shelf out of obligation rather than excitement. If the makers of "Toy Story 4" shared these anxieties, they've merged them into plot of this movie. Among other things, it's about a devoted playmate's fear that he's become obsolete, boring, not special anymore, and otherwise incapable of holding the attention of a child.

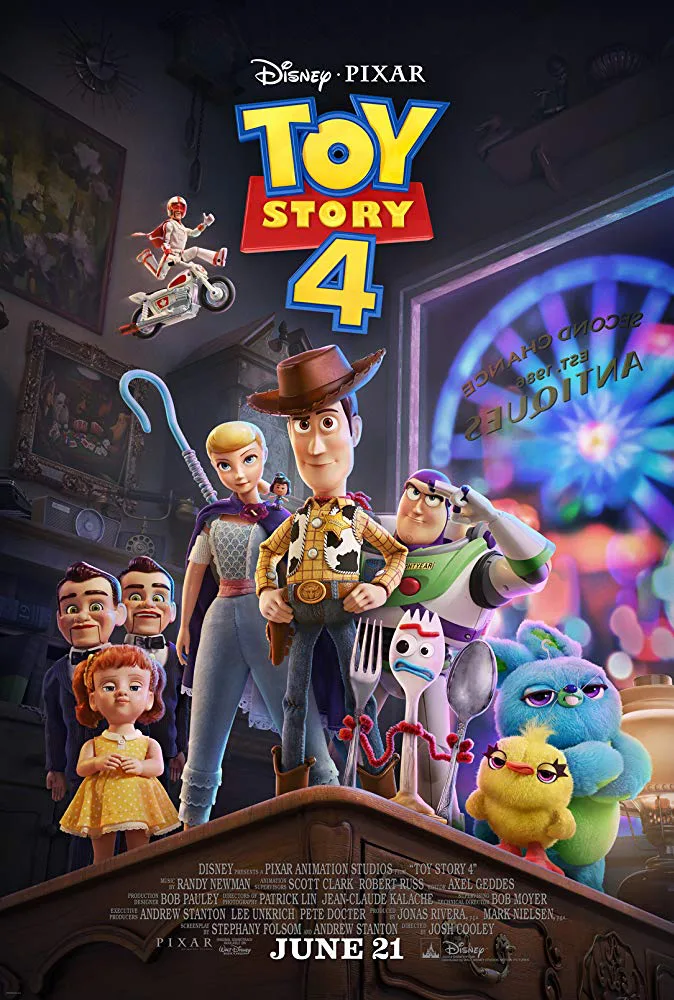

But, as old toy commercials used to promise: that's not all! Although the first part of the movie concentrates on the relationship between Woody and Forky (who have a long, uncut walk-and-talk that strangely evokes both "Of Mice and Men" and "Midnight Cowboy"), the rest of "Toy Story 4" distributes its attention democratically among playthings that we know from before, including Tim Allen's Buzz Lightyear and Joan Cusack's Cowgirl Jesse, and new toys that we meet during the family's week-long Winnebago road trip. The latter include Keegan Michael-Key and Jordan Peele as Ducky and Bunny, wisecracking plush collectibles that Buzz meets at a fairground ball-toss; Keanu Reeves as Duke Caboom, a Evel Knievel-styled motorcycle rider who describes himself as the greatest stuntman in Canada; and Christina Hendricks as Gabby Gabby, a 1950s-era talking doll whose voice box is broken, and spends her days ruling a desolate kingdom of unclaimed toys in an antique shop. (It wouldn't be a "Toy Story" film without a touch of the sinister, and Gabby provides it with help from her minions, a set of identical ventriloquist's dummies whose big heads tilt when they run.)

As the story unfolds, we're treated to all of the elements that we've come to expect, including a mission to rescue a missing or kidnapped toy, a climactic action sequence reuniting separated characters, and a moment where a toy hilariously breaks the rule against letting humans know they're alive. But on the whole, "Toy Story 4"—which was written by Stephanie Folsom and Pixar veteran Andrew Stanton ("Finding Nemo") and directed by Josh Cooley ("Inside Out")—breaks somewhat with tradition, in that it's less of a straightforward, linear comedy-adventure than a patchwork of scenes, moments, and groups of characters, unified more by shared themes and ideas than by any particular thing that happens. It's a stretch to call this a Robert Altman movie with little plastic toys, but darned if it doesn't get close to that sometimes.

Also in "Toy Story" tradition—perhaps more so than ever—this entry is flexible in its metaphors, in the way that dreams are flexible: i.e., a character or storyline can mean more than one thing at the same time. This allows the viewers to imprint their fears and dreams onto the material, and subtly change how they read a moment without contradicting themselves (or worrying that movie is contradicting itself).

Kids won't understand much of this, but they won't need to, because the film's surface level is designed to be legible to any child old enough to understand a tale told in images. (Listen during the opening Pixar logo for the sound of a small child laughing when the desk lamp turns to look at the audience; it's been happening since 1986.) Ultimately, anything these toys desire is driven mainly by the fact that they're toys, and the series has always been clear about what motivates them. They inhabit a world with rules and a code as clearly laid out as the ones in the John Wick and body snatchers and Batman franchises. The toys are all defined by their relationship to a child, whether it's a relationship that still is, once was, or hasn't happened (yet).

Once you get beyond that, things get curiouser and curiouser. The toys in the "Toy Story" films simultaneously stand in for children and adults (more the latter than the former—as "When She Loved Me" from "Toy Story 2," one of the saddest songs in film history, testifies). But Woody's specific mix of anxiety and depression here seems more like that of a grandparent than a parent. Woody's polite but frantic takeovers of Bonnie's playtime evoke a newly-employed senior citizen starting at a new workplace that's staffed mainly by younger folk who have their own way of doing things; and also a grandparent whose own kids grew up and left the house, and is now manufacturing a fresh sense of purpose by turning into a busybody who micromanages his granddaughter's life, and second-guesses her parents. Really, Woody didn't have to go to to kindergarten with Bonnie, and it's possible that his artistic midwifing of Forky caused new complications for him and his pals. It's like an older parent having (or adopting) a new baby, years after the first round has left the nest.

Even more so than in the first "Toy Story," where Woody feared his old-school charm would be overshadowed by a flashy new spaceman, or the second and third movies, which centered on toys' fears that children will mature and abandon them, the cowboy is fretting over the likelihood of forced retirement, followed by erasure. Fear of death, whether in body, spirit, or reputation, lingers over the movie, though never so heavily that you forget to laugh at the toys being silly.

This cowboy has a snake in his boot, and subtext in his text. Every time Woody prevents Forky from breaking away and leaping into a garbage can, or sneaking off Bonnie's pillow at night and sliding into the trash bucket near her bed, he's symbolically postponing his own extinction, which he avoided in physical fact at the end of "Toy Story 3" (that terrifying sequence in the furnace) but could still experience by being locked away in a glass case (by somebody like The Collector from "Toy Story 2") or placed on a dusty shelf in a small-town antique shop (which happens to many old toys here) or simply tossed in the back of Bonnie's closet and forgotten. An elder quartet of Bonnie toys—voiced by Carol Burnett, Mel Brooks, Carl Reiner, and Betty White—assure Woody that these things happen to all toys eventually.

The relationship of toys to kids, and kids to parents/grandparents, is widened out even more by a screenplay that considers the relationship of parents and children to society, and how that same society assigns worth to adults based on whether they've paired themselves off with a child. The secret, unheralded costar of "Toy Story 4," and the focus of its most emotionally complex scenes, is Bo Peep (Annie Potts), Woody's sweetheart, who went AWOL in "Toy Story 3" but gets her missing chapter filled in here. When Woody meets Bo Peep again, she's essentially a hard-edged but self-sufficient single lady, driving around in a motorized skunk toy, and treating her three-headed sheep as "kids" (kids are what you call baby goats, which is why they're named Billy, Goat, and Gruff—this series has linguistic as well as visual layers).

Bo Peep is an instinctive shepherd to lost lambs of all sorts, but she uses her crooked staff as a climbing tool and defensive weapon as well as a means of corralling unruly "children." And it seems a stretch to call her a born mom, because who's to say she wasn't actually "born" to be the person she is at this moment? "Who needs a kid's room when you can have all of this?" she asks Woody, sweeping her crook across the panorama of the fairgrounds. (We also learn her secret nickname for Woody, which is less heroic than he might like: "the rag doll.")

Without putting too fine a point on it, "Toy Story 4" lets Woody and Bo Peep have a running dialogue about whether you're more or less of a toy, or a happier or sadder example of a toy, if you have a child's name scrawled on the bottom of your foot. Their relationship encloses preoccupations of other characters, all of whom are grappling with nature vs. nurture, and whether a sense of purpose is something you find on your own or accept after society hands it to you—whether it's Bo Peep rejecting traditional "motherhood" (she's content to be a mom to her sheep) or Forky rejecting Woody's assertion that he's a toy rather than a utensil, or Ducky and Bunny and Gabby pining for children of their own because they've been conditioned to feel incomplete without them.

Gabby's longing is associated with her lack of a voice, which is about as on-the-nose as the film gets. She covets the intact voice box of Woody, who's had happy bonds with two children, and believes that if she can claim his voice for herself, she'll acquire his child-pairing mojo as well. "When my voice box is fixed, I'll finally get my chance," she tells herself. But it's to the film's credit that it never presents either Bo Peep or Gabby's world view as the only legitimate one. Both are allowed to experience their own, tailored kinds of contentment. And how sweet it is that, for the first time since the original "Toy Story," there are no outright villains here, even coded ones—just strong-willed antagonists whose psychology sometimes pushes them to do bad things.

Several characters are also in dialogue with some sort of inner voice, whether it's Woody speaking to himself in his own dialogue box, Buzz randomly punching every speaking button on his torso hoping to experience a self-communion as rich as Woody's, or Bo Peep communing with a tiny "best girlfriend" toy named Giggle McDimples (Ally Maki), who sits on her shoulder a la Tinkerbell or Timothy the Mouse, dispensing relationship guidance and negotiating advice. So what we have here is a movie that speaks simultaneously to us, to itself, to all of its predecessors, and to the culture that shaped it, and that it has helped shape.

Few blockbuster movie series are so likable and accessible to people of all ages and cultures, yet at the same time so rich in metaphor, philosophy, and dream language. And aside from Ripley in the first four "Alien" movies, it's hard to think of a protagonist of a sequential quartet of movies as loaded with myth and metaphor as Woody, a character who never changes size, color, shape, or voice, yet always manages to stand in for many things at once. This franchise has demonstrated an impressive ability to beat the odds and reinvent itself, over a span of time long enough for two generations to grow up in. It's a toy store of ideas, with new wonders in every aisle.