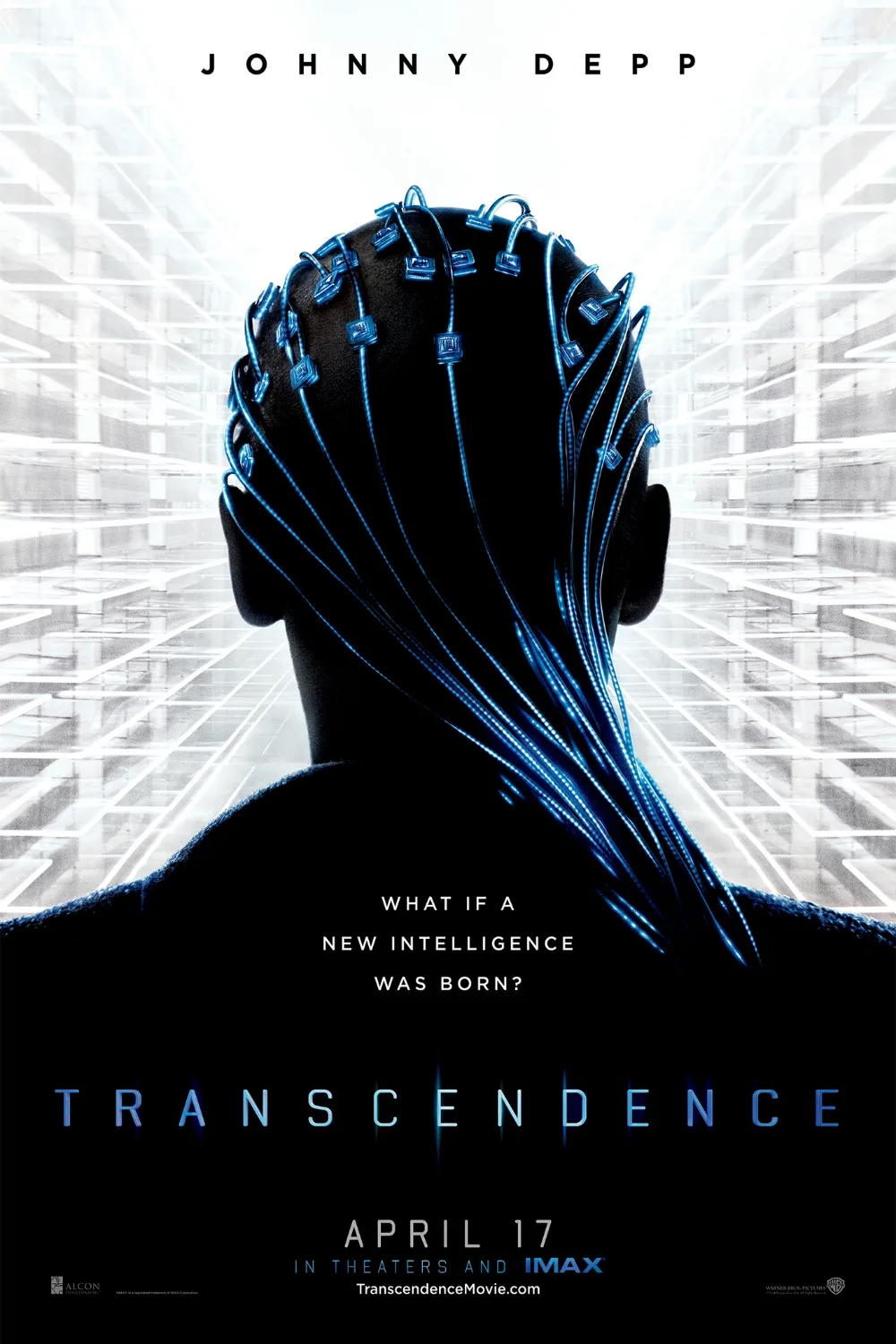

In Hollywood, the phrase "science fiction film" doesn't usually mean what it should. Most films sold with that designation aren't true science fiction, because they don't deal in ideas in a sustained, conscientious way; they don't extrapolate where we are and where we might be headed, and what it might mean for the human race intellectually, physically and emotionally. More often what you get are action or horror or superhero movies with a faint science fiction flavor—films that occasionally remind themselves to genuflect toward big themes when they aren't just having the characters run and jump and dodge explosions or be surprised by a monster lunging at them from the dark. "Transcendence," about a dying computer genius (Johnny Depp) who uploads himself in computerized form and achieves a problematic digital afterlife, is real science fiction. It explores its ideas with sincerity, curiosity and terrifying beauty (its director is Wally Pfister, longtime cinematographer for Christopher Nolan). This makes its failures all the more depressing. A bad film is just a bad film. A well-intentioned film that reaches for greatness and keeps falling on its face is some kind of minor tragedy.

How much do you want to know about the plot? Since a big part of the film's fascination lies in its unexpected storytelling rhythms, I'll try to restrict myself to elements already divulged in the trailer, even though I resented where the story ended up. Suffice to say that when the tale begins, Depp's character, a Steven Jobs-ian technology guru named Will Caster, has been at the vanguard of artificial intelligence research for some time. He and his wife Evelyn (Rebecca Hall of "Iron Man 3") have been trying to create a sentient machine with a personality, perhaps a digital facsimile of a soul, even going so far as to hook a prototype version up to a dying monkey and upload the contents of its brain. Next step: do it with a human. A terrorist organization headed by Kate Mara's Bree engineers a series of strikes against research labs to set the AI research back. They think that creating an omnipotent computer with a human personality is a bad idea. Imagine!

Caster is wounded in the 9/11 style, multi-pronged attack, taking a radiation-laced bullet and dying a few weeks later. And it's at this point—maybe a quarter of the way through the story—that "Trancendence" becomes intriguing. What we've got here isn't just a "Frankenstein"-like parable of scientific hubris run amok, but also the story of a grieving spouse who's reluctant to let go of her mate and tries to prolong his life artificially. The film's script, credited to Jack Paglen, takes its sweet time confirming whether the being uploaded into the neural network Will Caster or merely a digital copy, and if a copy, what sort.

Will, after all, did not upload himself, and as we all know, when a physical object is destroyed and then reassembled in some other form, it might retain the essence of the original thing, but it is not the same—and its shape and function might be altered, even tainted, by the expectations and agendas of whoever did the reconstructing, as well as by the means of reassembly and the materials used. You may be reminded of the end of Steven Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick's "A.I.", which distinguishes between an actual person and an idealized image of that person. You might also recall W.W. Jacob's short story "The Monkey's Paw."

As the real world merges with the virtual world, will reality become a mere adjunct of the virtual? Are the digital selves we create online truly extensions of us, or do they eventually take on lives of their own? The "Matrix" films, Spike Jonze's "Her" and many other science fiction movies addressed these questions; they're never far from this one's mind, and even when the film fails as drama, it keeps the imagination spinning. Will asks Evelyn to help him refurbish a dying desert town called Brightwood into a research facility that is to develop nanotechnology (machines as small as molecules) to repair and even replace flesh and alter nature. But is it really Will who's doing the asking? When we first meet him, he's a remote and in some ways inscrutable person (Depp's too-reticent performance makes him rather dull, actually), but post-digital conversion he becomes more controlling, building a love nest in which he constantly observes his beloved from computer screens as she pines for him, dines by candlelight, and sleeps.

"Are we sure it's him?" asks Will's best friend Max (Paul Bettany). "Clearly his mind has evolved so rapidly that I'm not sure it matters anymore," replies another computer genius, Tagger (Morgan Freeman), who fears something horrible is taking shape in the desert. Government forces, including an FBI agent played by Cillian Murphy, were originally allied against the terrorists, but now they're starting to wonder if they were on the wrong side. Brightwood is quite literally a god complex, headquarters for the puppet master Will. He posthumously manipulates reality from the protection of a cyberspace that might as well be his own personal Heaven.

The script is filled with Biblical allusions, some heavy-handed, others sly. It seems no accident that Brightwood, the place where miracles and seeming plagues occur, is located in the desert, or that the first three letters of Will's wife's name are identical to that of the character who ate the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge in the Book of Genesis. Pfister has thought the story out in terms of resonant images, some of which recur at key points in the story. Nourishing raindrops hide sinister secrets. Nano-bots swarm upward in black clouds like the locusts in "Days of Heaven." The in medias res beginning takes place in a garden where something miraculous has occurred. Scenes start or end with fades to white, as if alluding to four of the most famous words in the Old Testament: "Let there be light."

The landscape keeps being destroyed and reassembled, driving home the notion that as humankind evolves into a machine-human hybrid, all reality will become virtual, as easy to create, alter or erase as data on a hard drive. There's a constant undertone of anxiety about the possibility that human flesh is becoming as outdated as last year's iPhone. There's a longing for what Seth Brundle, the Frankenstein-like hero of David Cronenberg's "The Fly", called "the poetry of steak"—that intangible, miraculous something that makes humanity human.

If only "Transcendence" could get a handle on its attitude toward all of this. It's fine to want to explore and just sort of kick ideas around. Too often, though, the movie doesn't feel ambiguous or complicated, merely muddled and wishy-washy. It doesn't want to make Will, or Will 2.0, into a flat-out bad guy, a threat that has to be neutralized, and it doesn't want to scapegoat Evelyn, either, even though she's responsible for the digital re-creation of Will and seems to have a touch of Dr. Frankenstein herself. (This movie could have been called "Bride of Frankenstein," as in "The Doctor's Wife.")

The movie wants to warn us about the perils of playing God and of technological overreach, and it wants to concentrate those fears in one or two people for the sake of dramatic conflict; but by making this choice, it ignores the fact that in life, it's not one or two brilliant, irresponsible people actively doing things that eradicate privacy and alter reality: it's a sort of passive acceptance that eventually becomes adaptation, or evolution. Other people don't re-wire our brains, it just happens as we live more of our lives online. The problem isn't that some disturbed individuals want to turn us into machines against our will (ahem), it's that we don't have enough will to resist becoming more machinelike. We're slaves to convenience. Yes, you too. Just look at you right now, reading this on your computer, or your handheld phone, maybe in bed.

The most galling thing about "Transcendence," though, isn't its inability to get a handle on what, if anything, it wants to say about the enormous changes happening to the human race, it's the movie's ending, which seems calculated to reassure us that everything's going to be fine as long as the right people are in charge, especially if they're good looking. It's precisely that sort of blind acceptance of authority that got the world of "Transcendence" into a big mess in the first place, and that could bring this world, this "real" world, to ruin as well.