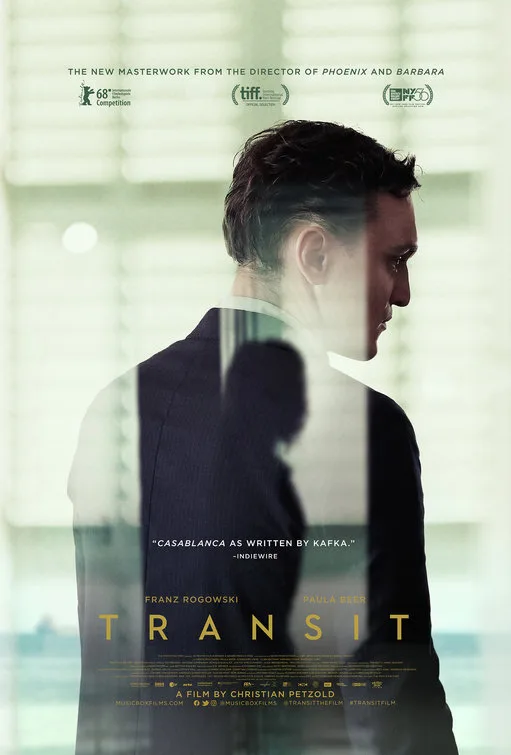

"Ports are places where stories are told," a character says in Christian Petzold's masterful "Transit," a film that closes out what the director has called his "Love in the Time of Oppressive Systems Trilogy" with "Barbara" and "Phoenix." At first, the parallels between "Transit" and "Phoenix" are striking. Both films are about identity and betrayal, and this film is based on a novel by Anna Seghers from the era in which "Phoenix" takes place: World War II Europe. As it unfolds and expands, "Transit" starts to echo several other clear inspirations from "Casablanca" to Kafka to even some more modern filmmakers like the Dardennes and Aki Kaurismaki, and yet this is very much a Christian Petzold film, first and foremost. It explores the themes that clearly fascinate him with his confidence of visual language and gift with performers. It is daring, riveting, and the first great movie of 2019.

Franz Rogowski stars as Georg, a German in Paris during an increasingly tense and violent occupation. Seghers' book was released in 1944 and set in 1942, so the story at that time was about the Nazis, but Petzold boldly chooses to update the story to modern times without really clarifying the threat. We just know that people are being rounded up and the country is increasingly unsafe. Before we've even seen the title card, police sirens have been heard three times. There's a sense of dread and urgency that's amplified by leaving the threat as undefined as active police cars in the street and enhanced discussion of things like travel papers. Especially with our current state of the world and its threats of violence amidst increased polarization, the themes of "Transit" have added resonance by making this a ‘10s story instead of a ‘40s one.

In Paris, Georg is asked to take two pieces of correspondence to a writer named Weidel. When Georg gets to the hotel, he finds a bathroom covered in the blood of the man he was supposed to meet, who has committed suicide. He takes the writer's belongings and jumps a train with a man named Heinz who has been injured. The two are headed to Marseilles to hop a boat to Mexico, where they might be safe, but Heinz dies on the journey. Two dead men will shape Georg's future, guiding him into the lives they left behind.

Throughout "Transit," Georg plays different roles. He's a father to a boy named Driss; he's a friend to a doctor named Richard; he eventually meets Marie Weidel and becomes a version of the person who left her behind; and he's even the film's (not necessarily reliable) storyteller, as the movie is narrated by a bartender who heard this tale from his best customer. "Transit" is essentially about a man caught in purgatory considering the lives he could have had as a writer, doctor, father, lover before he's allowed to move on to the next phase. He even reads one of the writer's stories about a man waiting to get into Hell only to be told that he's already there.

However, Petzold is too much of a romantic to allow Marseilles to become Hell. The already-great film reaches another level when Georg and Marie finally meet up. As she wonders why her husband never responded to the letter that she sent him, Georg becomes fascinated with her beauty, almost convinced he can save her. But if he leaves with her, he leaves behind the boy to whom he's become a father figure. So much of "Transit" is about people connecting and disconnecting. It is about the impact of fracture on both sides as one person asks who forgets first, "He who is left or she who is left behind?" And the impact of broken relationships is amplified by a sense that the world around these people is about to collapse. Who do you hold onto when the walls are coming down? Who do you choose to be when crisis knocks on the door?

Petzold's "Phoenix" was steeped in noir visual language, and this story could have been told in the same smoky, neon-lit style, but he conveys a lot of "Transit" in the bright light of Southern France, adding to the sense of confusion and disconnect that defines the film. Georg sometimes looks like a time traveler, and one could be forgiven for thinking this is a story of a Jew fleeing the Third Reich until Petzold drops in a shot from a surveillance camera or of a modern automobile. It adds both to the sense of purgatory—the idea that this is a man who doesn't belong and isn't sure where he's going—and the feeling that Georg is lost, not just in place but time. When he connects with Marie, it almost feels like he's connecting for the first time in his life, and yet this connection is based at least partially on a lie. Even in his truest moments, he is not exactly himself. He is a fill-in for a missing father or a missing husband.

Rogowski elevates the film by nailing a very difficult part—it's purposeful that Georg is in every scene in that it adds to the overall sense of confusion to limit our perspective to only his. Instead of presenting Georg as the cipher he could have easily become, Rogowski makes fully three-dimensional a protagonist who feels both classical in his Kafkaesque dilemma and yet also relatable in his emotions and actions. It's a great performance.

As he did with "Phoenix," Petzold completely sticks the landing, concluding with an almost mirror image of his last film's perfect closing shot. It's an ending that is both hopeful and uncertain. In other words, it captures the tone of a film about a man stuck between Heaven and Hell, and the stories he becomes a part of while he's there.