Film directors have to be a little like God, convinced that they have the correct answer to every question, and the responsibility to impose their opinion on everyone around them. Nice-guy directors - those praised for listening to their colleagues, keeping an open mind and encouraging their actors to improvise - rarely make great movies.

Great directors are routinely described as mean sons of bitches, but there is awe in the voices describing them.

John Huston was not, by most accounts, a nice guy. He ran roughshod over marriages, friendships and responsibilities. He had a habit of losing interest in a project halfway through, and he indulged his passions for horses, drink, gambling and women as if he had the divine right to be supplied endlessly with same. In his last years, crippled by emphysema, he nevertheless did present his daughter Anjelica with the role of her career in "Prizzi's Honor," and he grew closer to his other children, helping their careers while he somehow struggled through the making of "The Dead" - a brave film he correctly predicted would be his last.

Huston was a legend, larger than life, and his best films were about men something like himself. The actor who mirrored Huston the best was Humphrey Bogart in "The Maltese Falcon," "The Treasure of the Sierra Madre" and "The African Queen," and it is Huston's making of the "Queen" that supplied Clint Eastwood with the subject for "White Hunter, Black Heart." The original screenplay for "The African Queen" was adapted from C.S. Forester's novel by James Agee, a hard-drinking, hard-smoking writer who Huston expected to drink all night with him, then be his tennis partner in the morning and his collaborator in the afternoon.

This regimen probably hastened the heart attack that brought an end to Agee's work on the "Queen," and when Huston went to Africa with Bogart and Katharine Hepburn, he took along a young writer named Peter Viertel, who did the final version of the screenplay.

Viertel was a privileged observer to what has become one of the legendary location shoots of Hollywood history, and his novel from the 1950s, White Hunter, Black Heart, was obviously based on the experience. It did not paint a flattering portrait of John Wilson, the Huston character, who was more concerned with shooting an elephant than shooting a movie. After he finished the novel, Viertel told me, he sent it to Huston, who - to give him his due - said he enjoyed it and did nothing to prevent its publication. Huston was not a hypocrite and did not pretend to be other than what he was.

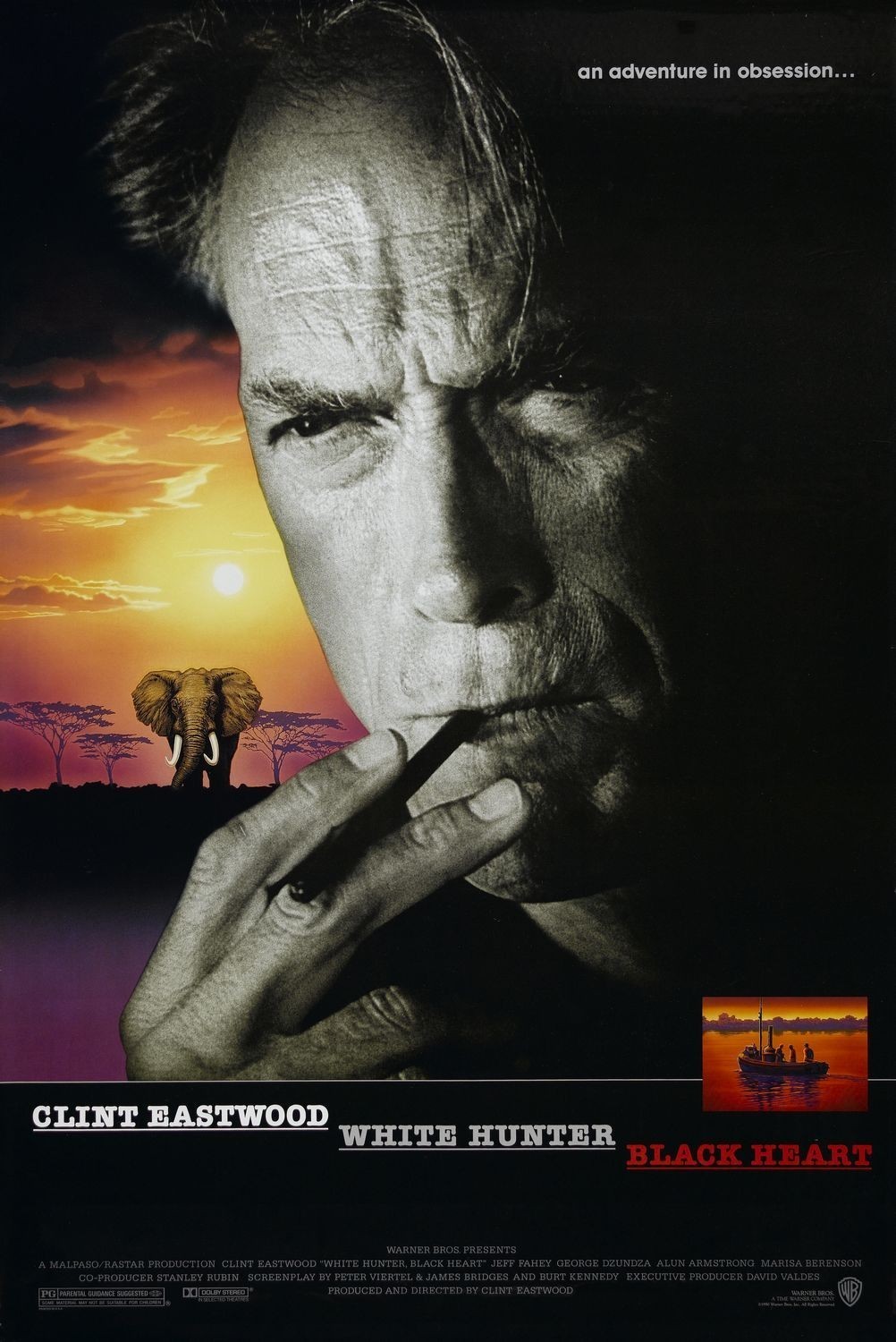

Now comes Clint Eastwood to produce and direct the long-delayed film of Viertel's book, and to star as John Huston, familiar accent and all. It must have taken some nerve for Eastwood to tackle this project. It is hard enough for a famous movie actor to disappear into a character who is not himself - but almost impossible for him to disappear into another famous character, into someone equally legendary and familiar.

In the early scenes of "White Hunter, Black Heart," Eastwood fans are likely to be distracted to hear Huston's words and vocal mannerisms in Eastwood's mouth, and to see Huston's swagger and physical bravado. Then the performance takes over, and the movie turns into one of the more thoughtful films ever made about the conflicts inside an artist. Huston emerges as a strong-willed, intelligent man who nevertheless places his own desires above his ideals, who rails at Hollywood's dishonesty and yet is not above keeping an expensive film on hold while he abandons his location to go elephant shooting.

Why does he want so badly to shoot an elephant? Perhaps because he has not shot one before. Perhaps to prove he is brave. Perhaps to give the elephant the privilege of being shot by John Huston. The obsession wraps itself around his evasions and self-justifications until the character's motive is hardly important; he is selfish enough that he will do it simply because he wants to.

There is a lot more to "White Hunter, Black Heart" than this description suggests. I especially enjoyed the verbal fencing matchs between Eastwood and George Dzundza, as his producer, and his confidences and confessions to Jeff Fahey, in the Viertel role. But what it comes down to is a man who puts his career on hold and keeps his colleagues waiting while he indulges in his own determined ego gratification.

Why did Eastwood make this movie? At one time I thought it was an attack on the Hollywood where he has functioned as a particularly successful outsider. Now I wonder if it isn't also intended as a contrast to some of the action heroes he's played in other movies.

The Eastwood hero almost always does what he damn well pleases. Here is a movie about a man who does what he pleases, but it doesn't make him a hero.