The best historical films, nonfiction or otherwise, are the ones that immerse us so completely in their time period that we become lost in them. Many directors I admire—such as Michael Haneke, Terry Gilliam and László Nemes—have criticized Steven Spielberg's 1993 landmark, "Schindler's List," for focusing on survivors of the Holocaust rather than the six million who perished. Yet every time I watch the film, I am profoundly shaken by its portrayal of self-righteous evil. The sense of loss is palpable because we are made to share in each victim's bewilderment as their life reaches a sudden and deplorable end. Janusz Kaminski's visceral cinematography and John Williams' restrained score place us directly inside the horror. There are hundreds of wrenching human vignettes weaved within the central narrative, and as in many of the great film epics, they resonate far more than any sequence involving the lead character himself. When I first saw the picture in junior high, I had to walk around in the sunlight for hours afterward, as if to affirm for myself that I was no longer in Auschwitz.

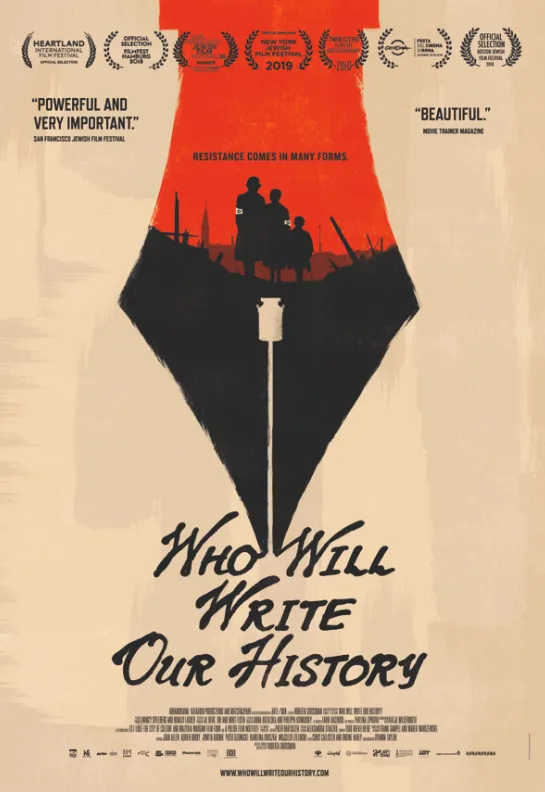

Roberta Grossman's latest documentary, "Who Will Write Our History," has an equally shattering and inspiring story to tell, yet its style continuously holds us at arm's length. Produced by Nancy Spielberg (sister of Steven), the picture unearths an archive of Jewish experiences under Nazi occupation that serve as perhaps the first precursor to her brother's own Shoah Foundation. Named "Oyneg Shabes," translating as "Joy of the Sabbath" to evade suspicion, this secret collection of documents compiles the testimonials of various Jewish citizens forced to live in the Warsaw Ghetto during WWII. The archive was spearheaded by Emanuel Ringelblum, a historian determined to preserve the truth of Jewish identity, thereby combating the hateful misinformation spread by Germans.

In one jaw-dropping clip of a Nazi-approved propaganda film, a schoolgirl laughs at the lice in her fellow peer's hair, only to be corrected by her teacher, who insists that the poor student can't help herself, considering her neighbors are Jewish. The footage then cuts to a shower room, where we see close-ups of Jewish men, who are portrayed as grotesque, disease-carrying beings. Hysteria generated by these sorts of flagrant lies fueled the division of Poland's capital into three quadrants, separating Germans and Poles from anyone branded with a Star of David. Around 400,000 inhabitants of the ghetto were estimated to have perished prior to its demolition following a heroic uprising in 1943, and only two contributors to the archive survived to see the end of the war.

One of them was Rachela Auerbach, a veteran journalist and critic who wrote extensively on the position of women in society and the double exclusion she experienced as a result of her gender and ethnicity. She's an enormously fascinating figure worthy of her own film, and there are times when Grossman's picture threatens to become just that, casting Jowita Budnik as Auerbach opposite Piotr Glowacki as Ringelblum. Yet not only are these reenactments fleeting, they also fall short of portraying their subjects in three dimensions. Just as 2014's Grossman/Spielberg collaboration, "Above and Beyond," failed to detail the plight of Palestinian refugees amidst its fist-pumping profile of Israeli pilots, "Who Will Write Our History" never gets under the surface of what makes its courageous archivists tick.

When Ringelblum asks Auerbach to remain in the ghetto and help in the soup kitchen rather than leave her hellish surroundings to join her family abroad, she agrees and the film moves on. What was it within the woman's mind and heart that led her to make such a profound sacrifice? Running at an all-too-crisp 90 minutes, the film doesn't explore its material thoroughly enough to be more than merely illustrative. Just when we've adjusted our eyes and ears to the reenactments, Grossman and her editors will jump to infinitely more compelling archival footage that doesn't come close to gelling with the actors. Top-drawer talent on the order of Joan Allen and Adrien Brody are brought on to read excerpts of Auerbach and Ringelblum's diaries, respectfully, but the solemnity of their voices clashes conspicuously with the urgency of the visuals. Even more intrusive are the historians—including Samuel Kassow, upon whose book the film is based—tasked with providing annotated context that reassuringly removes us from the immediacy of the atrocities.

At a time when Nazis, white nationalists and the KKK have been empowered by our own government, the mechanical structure of "Who Will Write Our History" is not only dated, it occasionally exudes the sterility of a museum installation. Not every film can be as extraordinary a feat as Peter Jackson's WWI doc, "They Shall Not Grow Old," yet aside from its innovative use of 3D and color to breathe new life into century-old footage, it demonstrated the power in allowing events and those who endured them to speak for themselves, rather than continuously be interrupted by talking heads. So closely did the film acquaint us with its subjects that we felt as if we were interacting with them, laughing at their jokes and wincing at their pain. Grossman's film will undoubtedly serve as an invaluable teaching tool, but as a work of cinema, it would've been much more powerful had it chosen to be either a narrative adaptation or a full-on documentary.

Among the faces framed in the reenactments, the only one that haunted me was that of Karolina Gruszka, so memorable as the "Lost Girl" in David Lynch's "Inland Empire," who has a similarly heartrending reunion in this film. The voice-overs are most effective at conveying the weariness of living under such unthinkable conditions, and Grossman deftly shows at the end how emotions tend to hit us once we've reached enough distance from our living nightmares. Allen also channels the frustration that Auerbach voices in her journals, as she finds her exhaustive efforts in the kitchen rendered futile by the overwhelming need. Most potent of all are the testimonials penned by Lejb Goldin (voiced by Jess Kellner), who converses with his empty stomach while observing how the bodies of children in the ghetto have deteriorated to the point where they resemble foxes, dingos and kangaroos. "Our howls are those of jackals," he writes, "but we are not animals."

Regardless of its missteps, Grossman's film should be seen as a necessary introduction to a multitude of stories warranting greater analysis. As Ringelblum himself notes, "the life of every Jew during the war is a world unto itself," and how eternally blessed we are that the Oyneg Shabes archive prevented the hell of the Holocaust from silencing their voices. There's a distinct through line that can be drawn between this film and Grossman's previous (and superior) feature co-directed by Sophia Sartain, "Seeing Allred," another story of Jewish heroism currently streamable on Netflix. Yes, the picture occasionally verges into hagiography, yet it's still a riveting look at the woman—attorney Gloria Allred—who embodied the force of #MeToo decades before the hashtag went viral. Her legacy exemplifies how sharing one's story can begin to heal the ills of a corrupted society. Taking ahold of one's narrative is all the more crucial in our current cultural moment, when xenophobia is being upheld by those occupying the White House. Just imagine the archive currently being compiled by those incarcerated along the U.S.-Mexico border.