"Xanadu" is a mushy and limp musical fantasy, so insubstantial it keeps evaporating before our eyes. It's one of those rare movies in which every scene seems to be the final scene; it's all ends and no beginnings, right up to its actual end, which is a cheat.

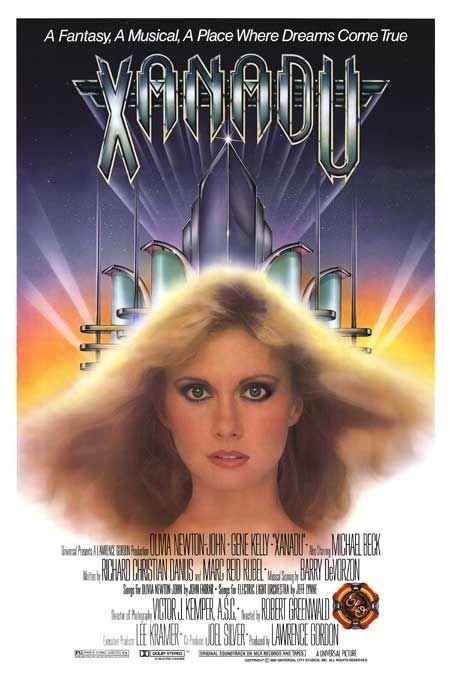

There are, however, a few - a very few reasons to see "Xanadu," which I list herewith: (1) Olivia Newton-John is a great-looking woman, brimming with high spirits, (2) Gene Kelly has a few good moments, (3) the sound track includes "Magic," if you haven't heard it enough already on the radio, and (4) it's not as bad as "Can't Stop the Music."

It is pretty bad, though. And yet it begins with an inspiration that I found appealing. It gives us a young man (Michael Beck) who falls in love with the dazzling fantasy figure (Newton-John) who keeps popping up in his life. Beck works as a commercial artist, designing record album covers, and when he tries to include Olivia in one of his paintings he gets into trouble at work.

That's ok, because he's met this nice older guy (Gene Kelly) who's very rich and wants to open a nightclub like the one he had back in New York in the 1940s. Kelly used to be a sideman in the Glenn Miller Orchestra (and also in the Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey bands, having apparently missed the Miller band's fatal last flight). In a quietly charming fantasy scene, he sings a duet with his old flame, the girl singer in the old Miller band-and, lo and behold, it's Olivia Newton-John.

That means both men are in love with the same dream girl, who, we discover, is not of this earth. They team up to convert a rundown old wrestling amphitheater into Xanadu, a nightclub that will combine the music of the 1940s and 1980s. And that is the whole weight of the movie's ideas, except for a scene where Michael Beck visits Olivia in heaven, which looks like a computer-generated disco light show.

Well, Hollywood musicals have been made with thinner plot lines than this one, but rarely with less style. The movie is muddy, it's underlit, characters are constantly disappearing into shadows, and there's no zest to the movie's look. Even worse, I'm afraid, is the choreography by Kenny Ortega and Jerry Trent, especially as it's viewed by Victor Kemper's camera. The dance numbers in this movie do not seem to have been conceived for film.

For example: When Beck and Kelly visit the empty amphitheater, Kelly envisions a '40s band in one corner and an '80s rock group in another. The movie gives us one of each: Andrews Sisters clones in close harmony, and the Electric Light Orchestra in full explosion. Then the two bandstands are moved together so they blend and everyone is on one bandstand, singing one song. It's a great idea, but the way this movie handles it, it's an incomprehensible traffic jam with dozens of superfluous performers milling about.

The Ortega-Trent choreography of some of the other numbers is just as bad. They keep giving us five lines of dancers and then shooting at eye level, so that instead of seeing patterns we see confusing cattle calls. The dancers in the background of most shots muddy the movements of the foreground. It's a free-for-all.

The movie approaches desperation at times in its attempt to be all things to all audiences. Not only do we get the 1940s swing era, but a contemporary sequence starts with disco, goes to hard rock, provides an especially ludicrous country and Western sequence, and moves on into prefabricated New Wave. There are times when "Xanadu" doesn't even feel like a movie fantasy, but like a shopping list of marketable pop images. Samuel Taylor Coleridge dreamed the poem "Xanadu" but woke up before it was over, a possibility overlooked by the makers of this film.