So asks little Yang-Yang, the 8-year-old boy in "Yi Yi," a movie in which nobody knows more than half the truth, or is happy more than half the time. The movie is a portrait of three generations of a Taiwan family, affluent and successful, but haunted by lost opportunities and doubts about the purpose of life. Only rarely is a film this observant and tender about the ups and downs of daily existence; I am reminded of "Terms of Endearment." The hero of the film is NJ, an electronics executive with a wife, a mother-in-law, an adolescent daughter, an 8-year-old son and a life so busy that he is rushing through middle age without paying much attention to his happiness. He's stunned one day when he sees a woman in an elevator: "Is it really you?" It is. It is Sherry, his first love, the girl he might have married 30 years ago. Now she lives in Chicago with her husband, Rodney, an insurance executive, but she follows him fiercely to demand, "Why didn't you come that day? I waited and waited. I never got over it." Why didn't he come? Why did he marry this woman instead of that one? It is a question raised in the first scene of the movie, at another wedding, where a hysterical woman apologizes to the mother of the groom: "It should have been me marrying your son today!" Perhaps, but as a character observes near the end of the film, if he had done things differently, everything might have turned out about the same.

The family lives in a luxury high-rise. We gradually get to know its members and even the neighbors (one couple fights all the time). The mother-in-law has a stroke, goes into a coma, and the family takes turns reading and talking to her. One day NJ (Wu Nienjen) comes home to find his wife, Min-Min (Elaine Jin), weeping: "I have nothing to say to Mother. I tell her the same things every day. I have so little. How can it be so little? I live a blank. If I ended up like her one day. . . ." Yes, but one day, if we live long enough, we all do. Talking to someone in a coma, NJ observes, is like praying: You're not sure the other party can hear, and not sure you're sincere.

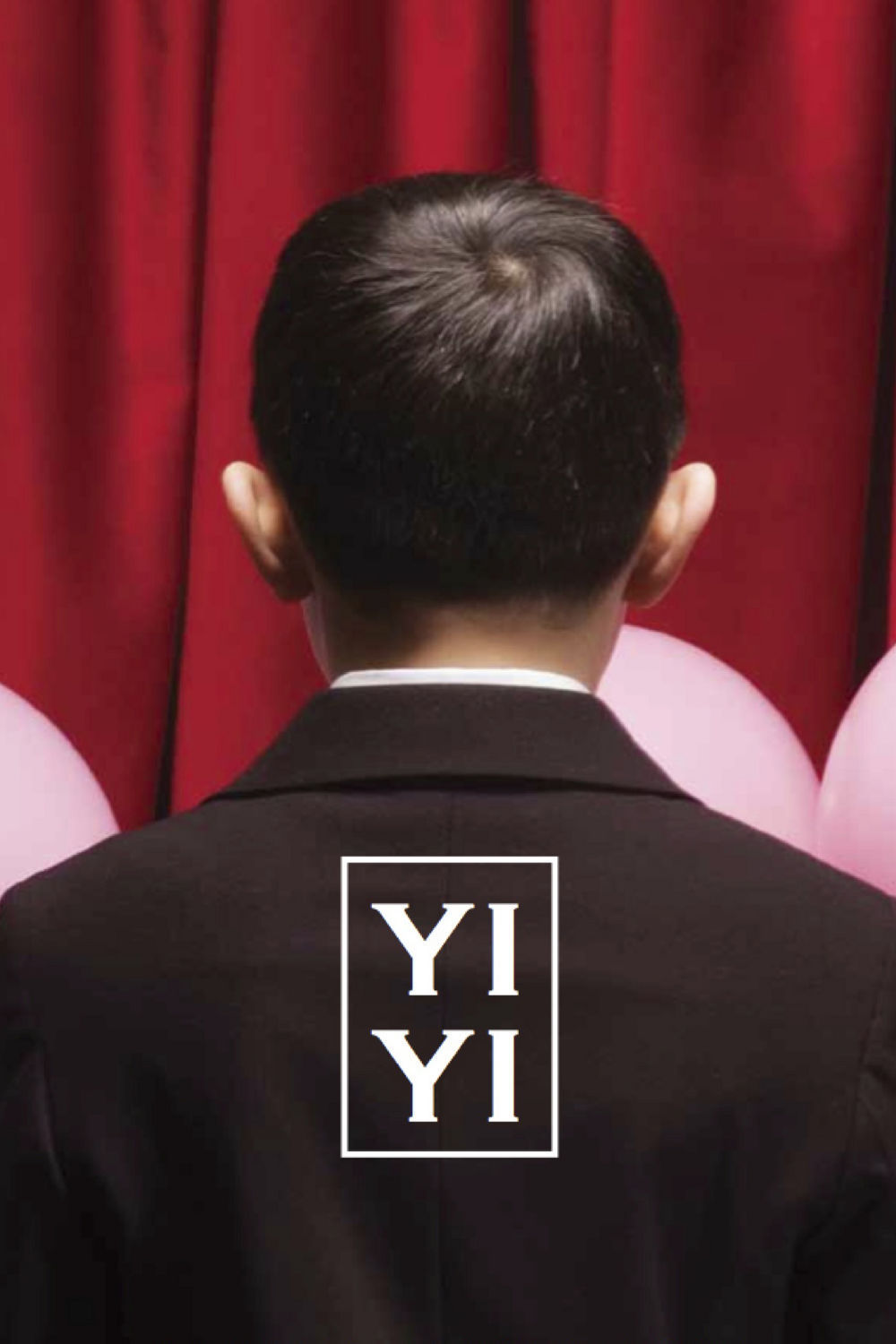

Little Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang) is too young for such thoughts and adopts a more positive approach. He takes a photo of the back of his father's head, since the father can't see it and therefore has no way of being sure it is there. And he takes photos of the mosquitoes on the landing outside the apartment, sneaking out of school to collect the prints at the photo shop (his teacher ridicules them as "avant-garde art").

Meanwhile, NJ is visited by memories of Sherry. Should be have married her? One of his few confidants and friends is a Japanese businessman, Mr. Ota (Issey Ogata); it is a measure of the worlds they live in that their conversations must be conducted in English, the only language they have in common. They sing in a karaoke bar, and then Mr. Ota quiets the room by playing sad classical music on the piano. Late one night, returning to a darkened office, NJ telephones Sherry (Ke Suyun). She wonders if they should start all over with each other.

NJ's teenage daughter Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee) is also considering cheating, with Fatty (Yupang Chang), her best friend's boyfriend. They actually check into a love hotel, but "it's not right," he says. That's the thing about life: You think about transgressions, but a tidal pull pushes you back toward what you know is right.

The point of "Yi Yi" is not to force people into romantic decisions. Many mainstream American films are impatient; in them, people meet, they feel desire, they act on it. If you step back a little from a movie like "3000 Miles to Graceland," you realize it is about stupid, selfish, violent monsters; the movie likes them and thinks it is a comedy.

Our films have little time for thought, and our characters are often too superficial for their decisions to have any meaning--they're just plot points. But the people in "Yi Yi" live considered lives. They feel committed to their families. Their vague romantic yearnings are more like background noise than calls to action. There are some scenes of adultery in the movie, involving characters I have not yet mentioned, but they come across as shabby and sad.

The movie is about the currents of life. But it's not solemn in a Bergmanesque way. NJ and his family live in a riot of everyday activity; the grandmother in a coma is balanced by Yang-Yang dropping a water balloon on precisely the wrong person. Some scenes edge toward slapstick. Others show characters through the cold hard windows of modern skyscrapers, bathed in icy fluorescence, their business devoid of any juice or heart.

There was a time when a film from Taiwan would have seemed foreign and unfamiliar--when Taiwan had a completely different culture from ours. The characters in "Yi Yi" live in a world that would be much the same in Toronto, London, Bombay, Sydney; in their economic class, in their jobs, culture is established by corporations, real estate, fast food and the media, not by tradition. NJ and Yang-Yang eat at McDonald's, and other characters meet in a Taipei restaurant named New York Bagels. Maybe the movie is not simply about knowing half of the truth, but about knowing the wrong half of the truth.

"Yi Yi" was named best film of the year by the National Society of Film Critics.