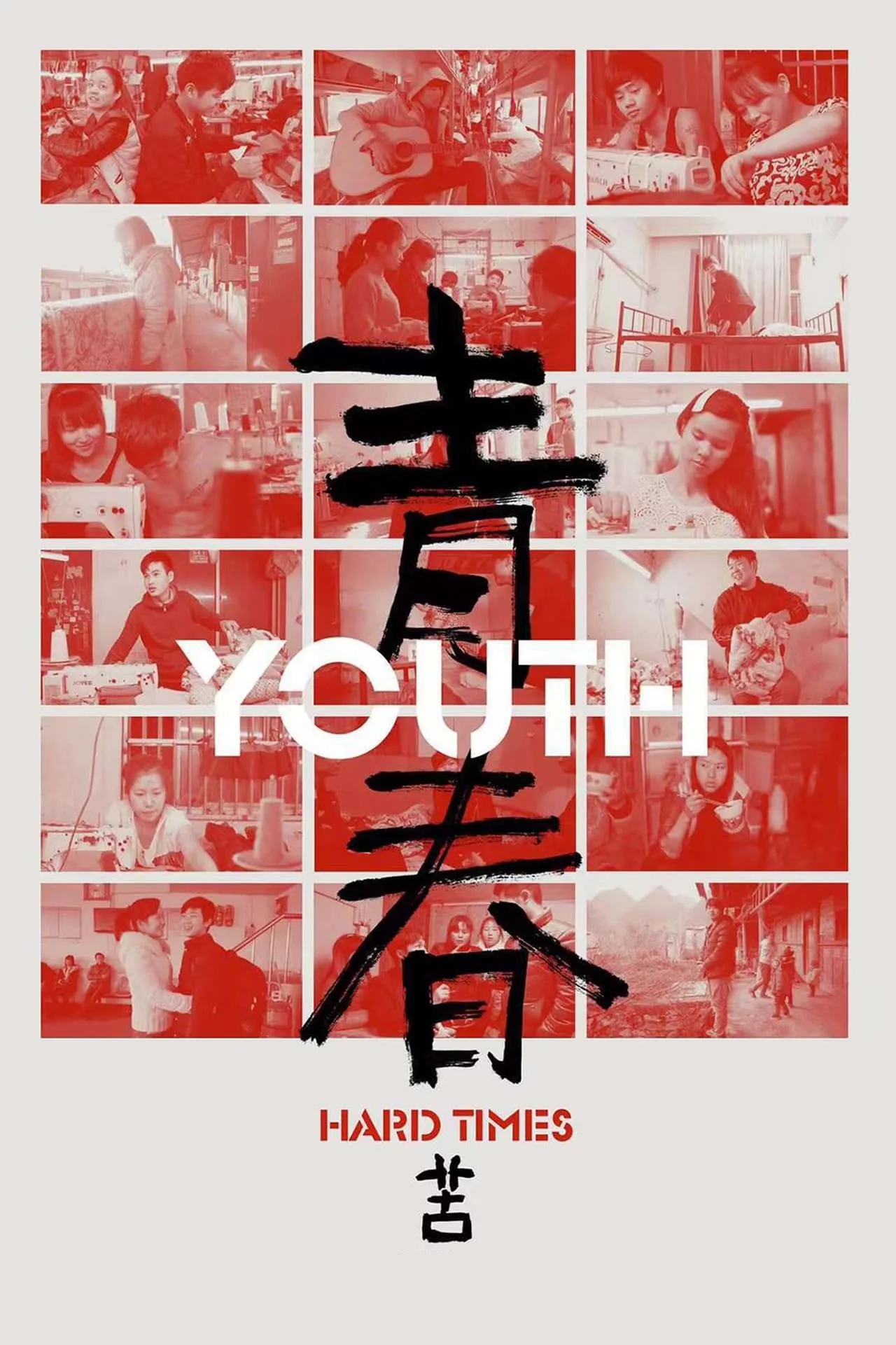

Time moves at its own pace in the almost four-hour-long Chinese garment industry documentary "Youth (Hard Times)," an overwhelming and often impressive mosaic portrait of young migrant laborers who live and work in the township of Zhili, mainland China's primary source for domestically produced children's clothing. Director Wang Bing and his editor Dominique Auvray shot 2,600 hours of footage over five years (2015-2019), during which time they observed and lived with an amorphous group of skilled but largely overworked and unprotected twenty-something workers. For the most part, Wang and Auvray successfully captured and re-assembled slivers of their subjects' daily lives; viewers can also see the limits of what could and couldn't be expressed on camera.

"Youth (Hard Times)" continues a kind of experimental narrative that began in last year's "Youth (Spring)" and concludes in the soon-to-be released "Youth (Homecoming)." Various workers' precarious working and living conditions are broken down into episodic scenes that represent individual voices as parts of an interwoven whole. These workers express themselves with the same (or similar enough) language, daydreaming, flirting, chain-smoking, and negotiating among themselves with adolescent fervor and a uniquely unerring combination of naiveté and fatalism.

Half-cocky and half-doomed, Wang's laborers hail from the outer provinces and also share the same technical skills. The quality of their work may not be considered good enough to export beyond China, but they still know their time's worth because they have to. Zhili's workers rattle off numbers—quotas, measurements, and earnings—with disarming ease. They're well aware of the difference between their bosses' miserly pay rates and their groups' prodigious output of denim and Mickey Mouse-patterned garments, and in "Youth (Hard Times)," they also try to negotiate for better pay. That doesn't go well, as you might imagine from the movie's title, but you can still see why Wang's subjects have to try to protect themselves anyway.

Rather than re-cast Zhili in a miserablist haze of constant work and free-floating anxiety, Wang and his colleagues rifle through pockets of ambient tension and excitement for the sake of establishing just how uncertain life seems to be at this particular moment in time. One worker (21) can't get paid by his stingy manager or domineering wife simply because he can't produce his paybook. Later, we see the violent aftermath of this conflict, which leaves several laborers wondering if they'll be paid for the work they've already completed. They also tease each other and fight among themselves whenever they're not bartering or fretting over their livelihoods, which reminds viewers, through halting speech and so much dead air, that these are young people who happen to be doing specialized work at a dizzying clip. One worker tells another that she wants to quit. Her colleague admonishes her mercilessly: "You only have yourself to blame[…]in this line of work, you have to be more careful."

The most convincing details in both "Youth (Hard Times)" and "Youth (Spring)" can be seen in the limits of the camera frame and the layers of the soundtrack's mix. Wang and Auvray carefully stalk and unostentatiously frame their subjects as they carefully navigate Zhili's spartan dormitories, stairways, side streets, and workspaces. The slap-shuffle of flip-flops on concrete floors provides a nice compliment to the workers and their supervisors' typically overflowing cross-current of dialogue. A drawn-out and only partly filmed negotiation for better pay is one of the movie's dramatic highlights.

There's seemingly more at stake in "Youth (Hard Times)" than there was in "Youth (Spring)," which makes time move a little faster in this middle installment of Wang's sprawling trilogy. There are also a few more scenes in "Youth (Hard Times)" where Wang's subjects acknowledge his and Auvray's presence by glancing nervously at the camera or by pausing for a long while before either initiating or picking up uncomfortable conversations. "Youth (Hard Times)" may be the most accessible entry in Wang's "Youth" project, but it's still not an easy sit.

If you've never seen a Wang Bing movie before, you might want to first catch up with "Bitter Money," the absorbing 2016 documentary that Wang made as a sort of proof of concept for what would eventually become the "Youth" trilogy. You should also make time for "Youth (Hard Times)" if only to see Wang and Auvray try and mostly succeed at capturing the wearying passage of time in Zhili. You'll never be able to forget that you're watching a narrativized work of non-fiction, but you may still find yourself marveling at how close Wang and Auvray seem to have gotten to their subjects. This one stands out not only because it's the fittingly agonizing climax to Wang's trilogy but also for its sheer wealth of heartbreaking and totally convincing details.