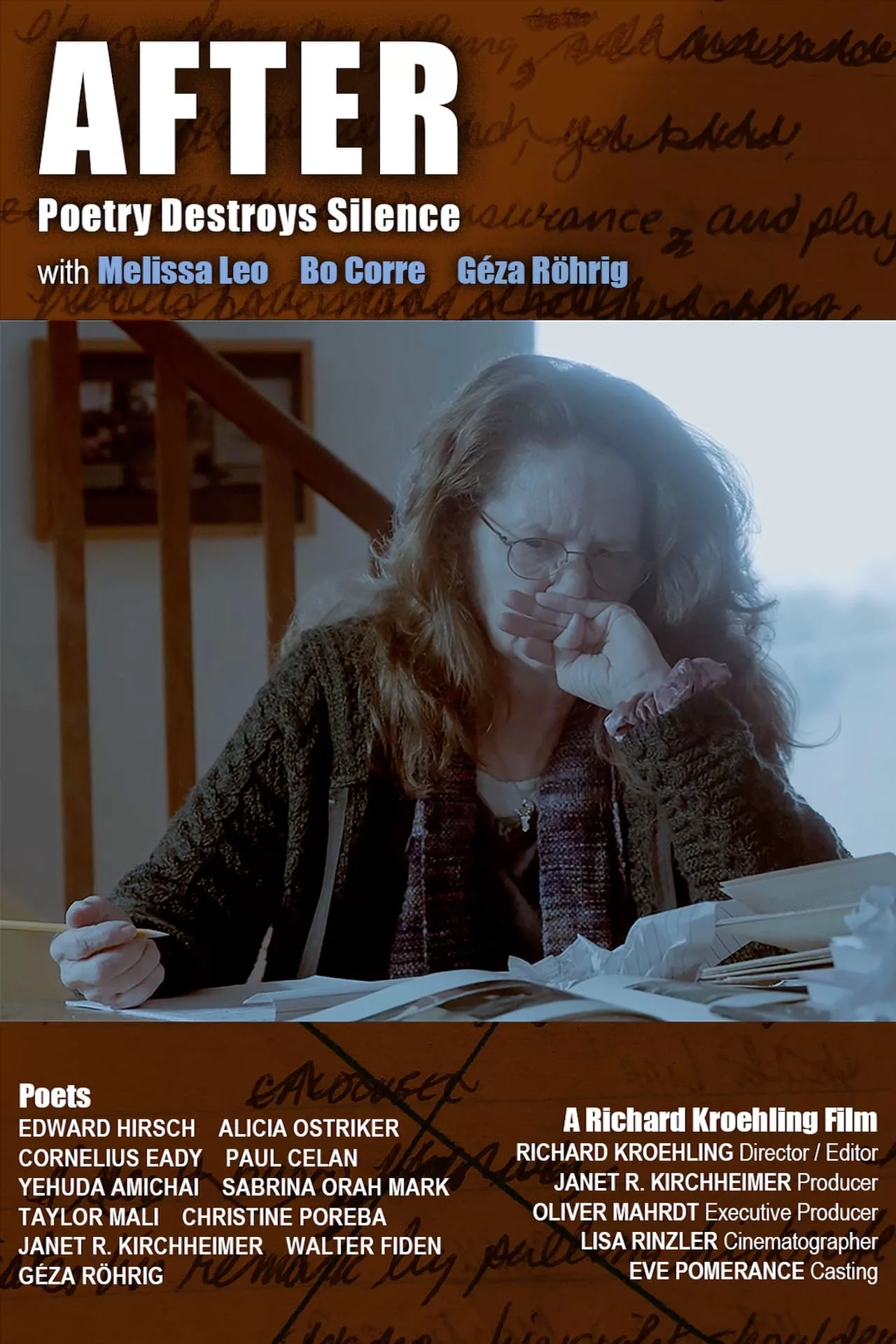

"After: Poetry Destroys Silence" is a documentary that argues that poets are as crucial to processing unthinkable tragedy as historians. The film's look and sound are lyrical, providing an apt setting for the poets who recite their work and discuss the kind of communication that fills in the gaps left by recitations of fact, archival images, or dramatic re-enactments.

As we approach the moment when there will no longer be living witnesses to WWII and the Holocaust, we still struggle to comprehend a time when Nazis tried to exterminate an entire religious community and others they considered unfit, including Roma, LGBT, and people with disabilities. Trying to understand the past can be like the blind man and the elephant, each touching just one part of the animal and thinking he understands it all. It takes every possible form of storytelling to connect us to the lived experience of those who were there.

Historians dig through archives and write papers about what they find. Museums show us artifacts with helpful explanatory wall cards. There are plays, ballets, operas, oral histories, documentaries, and narrative films. Every year, there are new movies about WWII and the Holocaust, including 2024's "Blitz," the upcoming "Kristallnacht," and last year's "Irena's Vow" and "One Life" as well as the Oscar winners "Oppenheimer" and "The Zone of Interest" (which was followed this year by a documentary about the same story, "The Commandant's Shadow"). Articles reporting on today's debates about candidates and policies still use the events of WWII as reference points to calibrate our understanding and reinforce our commitment to remember and learn from the conflicts and tragedies of the past.

There are poets, whose work is a combination of song, speech, sermon, and sometimes spit. Some process their connection to the Holocaust, those who survived and those who perished. In this film, poets talk about why and how they tell stories of incomprehensible inhumanity and loss, their faces and voices as gripping as any Hollywood luminary. The poems are accompanied by visual and aural poetry. Words float across the screen with images, some abstract, some illustrative, some impressionistic, with evocative sound engineering by Helge Bernhardt. Fingers tap the round keys of an old Underwood typewriter, snow gently falls past the bare branches of a tree, and archival photos show us people who did not survive.

The film is a response to philosopher Theodor Adorno, who said, "To write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric." He thinks that because no art can fully convey the horror of the Holocaust, it is disrespectful to try. The film rebuts that idea with a quote from Charles Bukowski, "Poetry is what happens when nothing else can." That does not mean that poetry is the only way to communicate; it can fill in the gaps that even the most accurate history and the most telling drama cannot.

We hear Janet R. Kirchheimer, a daughter of Holocaust survivors, read a poem reflecting on her growing understanding of her parents' experience from childhood to adulthood. She reads, "How I Knew and When," her mother joining in on the last line, "Home is anywhere they let you in."

Edward Hirsch is the author of the best-seller How to Read a Poem: And Fall in Love with Poetry, as well as collections of his own poems and editor of the anthologies 100 Poems to Break Your Heart. Even his dialogue has the precision and cadence of poetry and myth (his PhD is in Folklore). Hirsch tells us, "The obligation of poetry to respond to certain kinds of horror. The Holocaust is a kind of test case because it defies language and defeats language and yet language has to respond. It's our job as poets to remember what happened. Documentaries and acts of reportage won't give us reflections on how to feel." He recognizes that we can only speak the language of our own time; it would be false and pretentious to try to tell the story of events of the 1940s as though we were writing a first-person contemporary description. But the distance we have has its own perspective and its own urgency.

Sabrina Orah Mark, the granddaughter of survivors, writes in more abstract, indirect terms. The poem she shares is titled Kaddish, after the Jewish prayer of mourning, and it is a reference to a shiva, the gathering of those who are grieving. It is one of the film's best examples of why poetry should be heard rather than read. The sounds are as significant as the word, with the line, "All I could hear was shiver, shiva, shhh." The film includes a poem from a Holocaust survivor, who believes "nothing is hopeless" but viscerally describes the desperation of hunger: "all these details are nailed into my head…I took the ground and ate it."

And there is another from a survivor named Paul Celan. He spoke six languages and worked after the war as a translator of poems in English by Robert Frost and Emily Dickinson. Still, he chose to write his own poems "in the language of the people who murdered his family" before ending his life in 1970. We also hear an infinitely poignant poem by an anonymous author found after the war in a milk can buried under the Warsaw ghetto. As Hirsch points out, poetry has been written in every culture throughout history. The person who buried that poem was deprived of freedom, of food, and eventually of life, but writing a poem that might someday share those feelings provided some comfort, some voice.

Taylor Mali, best known for his viral poem about what teachers make ("I make kids wonder/I make them question/I make them criticize/I make them apologize and mean it"), shares his poem about the most personal and devastating grief, the suicide of his wife.

The poet Alicia Suskin Ostriker tells us what only poetry can do: "Poetry goes below the surface….in a way that journalism and academic language can never do. Poetry is what poets do with trauma." She explains that the economy of poetry, the very aspect that can initially seem obscure, invites us to engage. "What is not said is just as important because it pulls the audience in and makes them be co-creators of the poem." In the same way, this film immerses us and makes us participants in sharing the poets' words.