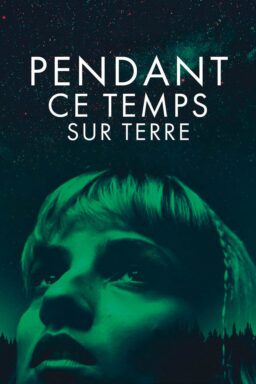

How far would you go to see the loved ones you've lost again? What if it cost the lives of others? How do you make the calculus of whose lives to trade? Amid all the heady sci-fi trappings and dreamlike blend of animation and live-action in Jérémy Clapin's follow-up to "I Lost My Body," "Meanwhile on Earth," lies this mournful question. Grief and loss can take hold of your soul, not unlike a possession; what Clapin explores here is the temptation of reconnection, and what that oft-impossible yearning can do to a person.

For Elsa (Megan Northam), that loss comes in the form of her astronaut brother Franck (voiced by Sébastien Pouderoux), who vanished three years ago on a deep-space mission. He is honored with statues and plaques, but the hole he leaves in Elsa's life is too great to endure. Consumed by grief, she spends her days stuck in the same dead-end job at the elder care facility her mother runs, doodling her daydreams of life with her brother—brought to life by black-and-white animated interludes reminiscent of '70s anime. She spends her days in a haze, wanting absolutely nothing save the prospect of seeing Franck once more.

One night, her torturous wish threatens to come true; a mysterious alien voice (Dimitri Doré) materializes in her head, alongside a gloopy alien "seed" that lodges in her brain and communicates with her. They claim they have Franck and will return him to her. Only problem is, she has to help the aliens occupy the bodies of five dead humans, at the cost of their lives. Seeing relief from her pain, she naturally acquiesces, turning "Meanwhile" into a heady mix of mood piece and campy body-snatcher sci-horror as Elsa tracks down more deserving, and then less deserving, targets for her new masters.

That mix largely works, at least for most of the film's runtime; Clapin is clearly preoccupied, like Elsa, with what it means to mourn and how we trap ourselves in our grief. Northam conveys volumes in her wide-eyed, brittle performance, imbuing Elsa with the kind of numbing desperation that comes with closing ourselves off from the world after a loss. Elsa's deep wounds make her the perfect Renfield for the alien's plans, the thought of seeing Franck again being the perfect lever to facilitate an alien invasion. Northam plays every new turn with a raw-nerve sensitivity familiar to anyone who's lost themselves in losing someone, and it's compelling to watch.

Clapin's dreamy mise-en-scene matches Elsa's own ethereal adriftness, Dan Levy's haunting, choral-and-synth score echoing alongside Robrecht Heyvaert's cold, alien cinematography. It all gives off the feeling of a woman walking through the Earth as if it, itself, is an alien planet, Elsa an astronaut lost in the space of her own grief. Unfortunately, this distance is both the film's boon and major weakness: Clapin deals so much in atmosphere that we get little feel, over the film's 87 minutes, of who Elsa is as a person and what Franck meant to her outside her animated reveries. Elsa's initial attempts to cull the herd for her alien handlers start with cathartic, slasher-movie kills against lecherous loggers before becoming more anxious moral dilemmas about whether to kill less deserving prey. It's a powerful tightening of the film's central philosophical question, but Claplin's opacity as a filmmaker robs us of a lot of on-screen exploration.

"Not everyone finds their path," Elsa's mother advises in one of the film's later, more direct examinations of its premise. "We have to choose to be happy." "Meanwhile on Earth" is preoccupied with this notion, a fantastical look at the depths of heartache and what happens when we choose to turn away from a future for ourselves and live in the pain of what we've lost. There's little closure in the film's final minutes, which admittedly can frustrate. Still, maybe that's the most pointed observation we can make about grief; we can heal, move forward, and maybe even be whole again one day. But the ache never really goes away.