Clint Eastwood will be 92 next May.

Now. To take a particular kind of stock of this fact. The Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira lived to be 106. And he completed his final film in 2015, the year he died. So when we are talking about Eastwood's ostensibly late filmography, and we consider the speediness with which he completes his films—which some insist also yields slapdash results, the fake baby from 2014's "American Sniper" standing as Exhibit A—we can consider that he may actually have another 14 or 15 movies in him yet. That's worth noting when we're talking, as we are now, of his "late" filmography.

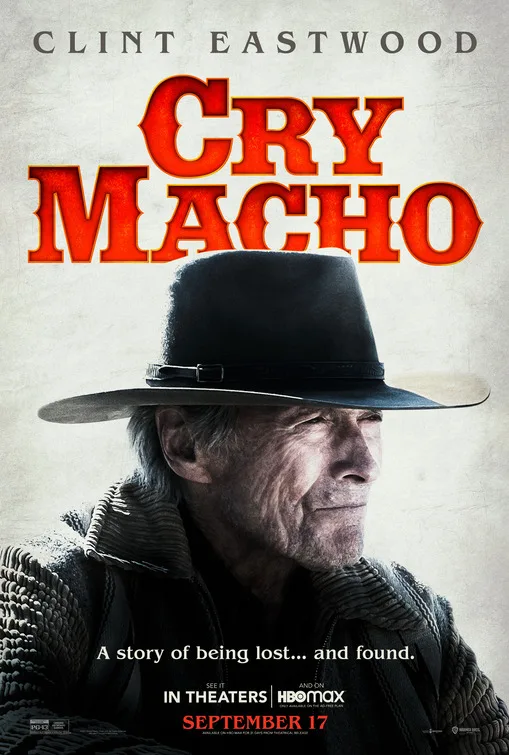

Because even if Eastwood keeps up his filmmaking pace for another decade or more, "Cry Macho," which he directed from a long kicking-around script by Nick Schenk and N. Richard Nash, and which began as a 1975 novel by Nash (and this movie adapts it very loosely, to say the least), will end up one of his more unusual films. Its title and trailer suggest a potentially blistering, and likely rueful, action thriller. The movie itself is something wholly other.

For its first 20 minutes or so, one may look through the fingers of a facepalm trying to figure out just what it is. Gorgeous vistas of Western sunrises and starkly beautiful desert plains alternate with story-establishing scenes in very awkwardly on-the-nose registers. Starting in 1979, the movie depicts Eastwood's Mike Milo showing up at the horse ranch of Dwight Yoakam's Howard Polk well after the lunch hour. Howard tells Mike he's late, and Mike says "for what?" Howard then lays into Mike with scrolls-worth of expository dialogue, evoking Mike the one-time rodeo star, mentioning the inevitable career-ending "accident," and so on. "Before the pills ... before the booze," Yoakam proclaims in decidedly declamatory tones, dropping the hammer with "You're a loss to no one." He fires Mike and then we cut to a year later, when, um, he re-hires Mike—asking him to go to Mexico and kidnap his now-teenage son, who lives with his hard-partying mother Leta in an abusive household. Mike takes the shady gig—he owes Howard still, for something.

Things remain awkward when Mike gets to Mexico and finds Leta in a mansion, attended by two bodyguards, and telling Mike he's welcome to the kid—a gambler, drinker, and cockfighter named Rafa (Eduardo Minett), and not even 14 yet—if Mike can find him. The hotsy-totsy Irresponsible Mother even tries to lure Mike to her bed. Which is a bit of a stretch. One thing Eastwood's continuing career on screen is teaching us is that there are discrete gradations of old. As written, Mike Milo ought to be a character in his late sixties to mid-seventies. As good as Eastwood may look, 90 or 91 is not late sixties to mid-seventies. In matters of personal intimacy, even if the spirit and the flesh are equally up to the task, the most game woman on earth is going to think twice about jumping the bones of a nonagenarian, lest she shatter them.

You're probably wondering when this movie gets good enough to warrant my rating. To be perfectly frank, it does require some patience if not indulgence. Mike discovers Rafa; Rafa is indeed a cockfighter and he's named his rooster "Macho." They make it out of a police raid on a cockfight and hit the road, one of Leta's bodyguards trailing them. Rafa is wide-eyed at the prospect of living on a Texas horse ranch—as Howard assured Mike, the kid is crazy about cowboys. As the two get to know each other, Mike expresses to Rafa his hard-bitten skepticism about over-valuing toughness—"macho" itself, as it was popularly called both north and south of the border in the period in which the film is set. This is all pleasing and a little predictable.

Where the film really blossoms is after the mid-section. After some narrow evasions of both bodyguards and cops, and some hasty car-switching, Mike and Rafa find themselves in a small Mexican town not too far from the border. They take shelter in a homey restaurant owned by a middle-aged woman named Marta (Natalia Traven) and later in a small shrine to the Virgin Mary on the outskirts of the town. The two come upon a horse ranch, where Mike offers his services in breaking the wild ones. He also teaches Rafa to ride, saying he won't be much use in Texas if he doesn't know how to ride.

Mike is good with animals, so soon the town locals start treating him as if he's a vet. Mike and Rafa meet Marta's grandchildren, one of whom is deaf; Mike can sign, and he makes an immediate, vital connection with the little girl.

These small events transpire in beautifully shot, unhurried scenes. This is Eastwood's version of pastoral. Mike pieces his ruined life back together in a sense. He finds pleasure in being of service to a community. The professed agnostic takes Marta's hand when she prays to begin a meal, and likes it. The simple sincerity about what's worthwhile in life is the movie's reason for being. Nothing more and nothing less.

Available in theaters and on HBO Max for 30 days starting Friday, September 17.