"The Line," the feature debut of writer-director Ethan Berger, won't tell you anything you likely don't already know about modern fraternity life. In fact, it spends its 100 minutes dutifully beating that drum (alongside Daniel Rossen's percussive, cheeky score), offering a crisp "The Social Network"-y drama about the predatory and stifling Greek culture that rapidly twists its young pledges into booze-and-coke-riddled miscreants. And yet, for all its comparative lack of insight, there's something intriguing about the ride, due chiefly to a pair of fascinating lead performances and a fatalistic sense of humor.

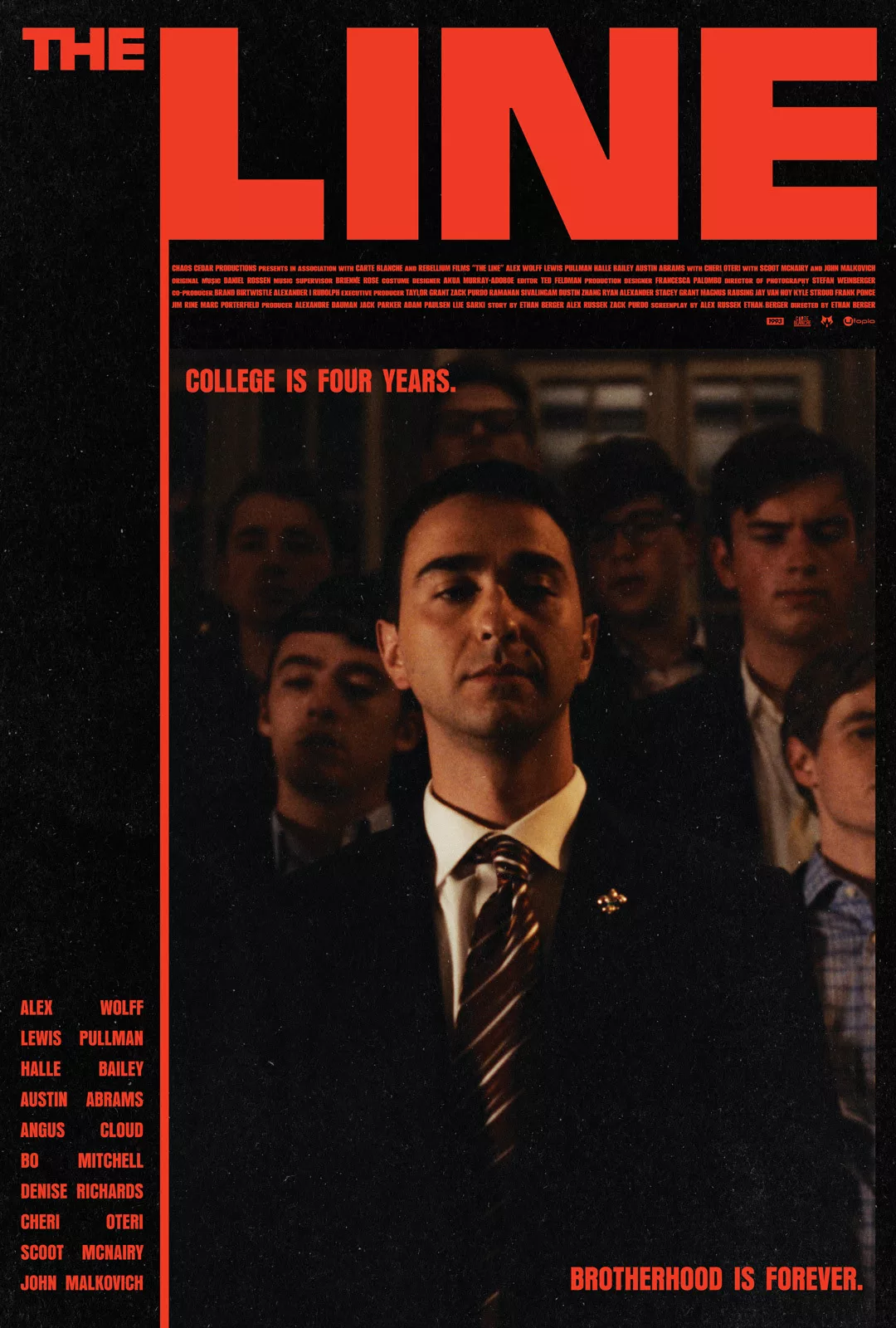

In its opening titles, we see a montage of fraternity class portraits throughout history, reams of smiling, smug, privileged faces, often dressed in suits, daring the audience to question the primacy Greek life is soon to gift them. As our protagonist, Tom (Alex Wolff), is all too aware, access to a fraternity community (and its famous alumni) gets you proximity to important people, relationship-building, career and even political opportunities. And so it goes as he enters his sophomore year at a Southern university, now a firmly entrenched member of Kappa Nu Alpha (or "KNA!" as its members shout, cult-like). He's already well set; he lives with his best friend Mitch (Bo Mitchell), a porcine party boy who's mostly in the frat because his dad (John Malkovich) comes from money, and his Florida accent has already warped into a long-voweled, Southern drawl that his exasperated single mom (Cheri Oteri) describes as "faux Forrest Gump."

Sure, it's a performance. But unlike many of his brothers, he comes from a working-class background, so he knows he has to play the game. So he schmoozes with Mitch's dad over dinner and cozies up to the quietly confident chapter president (Lewis Pullman) who's taken him under his wing. "Always align yourself with the best," Malkovich purrs over a restaurant table. "That's the recipe." This year will test him in ways he couldn't anticipate, particularly as Mitch's boorish antics clash with the natural social order of the frat and butt heads with a particularly rebellious pledge (Austin Abrams) who's uninterested in playing the humiliating hazing rituals the house has already racked up 17 violations performing.

As soon as Berger and co-writers Zack Purdo and Alex Russek's script treats you to the phrase, "Have you ever seen a fish on the wall with its mouth shut?" you know "The Line" is hurdling you to the inevitable consequence of KNA's coked-up bacchanalia, and the weight it will carry for Tom. But it's the hour or so leading up to that moment—a fateful escalation of all the violence Greek life teases—that impresses most. Berger lays out the pieces of KNA's specific quirks and habits nicely, and the dynamics each character falls into. It's all hypermasculinity, gay jokes, snorted lines of cocaine, and monologues designed after the big war speech from "Gladiator." There's an ethnographic approach to Berger's work, aided capably by Stefan Weinberger's moody cinematography (scenes in the frat house carry a sparsely-lit, almost haunted quality) to sell us on the insular dens of macho competition these frat houses become.

The cast is uniformly excellent, with some nice supporting turns from both young (Pullman, Abrams, Angus Cloud) and seasoned (Cheri Oteri, Denise Richards, Scoot McNairy) performers. But Wolff carries the thing mightily on his shoulders; Tom is a dunderhead, to be sure, but you can see the glimmers of goodness within him, or at least the slight scruples he develops when he finds himself in over his head. (Halle Bailey appears in a subplot as a more liberal-minded Black student whose presence both opens his eyes to non-frat perspectives and teasing from his brothers, but her scenes offer little beyond a moral sounding board.) The true discovery, though, is Mitchell's Mitch, whose weight and abrasiveness are clear sources of insecurity for him. He's roughly analogous to Piggy from "Lord of the Flies" or Gomer Pyle from "Full Metal Jacket"—the group punching bag whose recognition of his outsider status just sends him into more outsized behavior. He plays that insecurity well, creating a creature both loathsome and pitiable at the same time.

It might play out like a thriller at times, but there's no shortage of pitch-black humor; Berger invites you to guffaw at these buffoons as they razz each other over everything from golf cart rides to forgetting to order strippers for an off-campus retreat. (The reoccurring use of Eiffel 65's "Blue (Da Ba Dee)" puts a delectable button on the idiocy in which these pledges must partake.) But by the end, it becomes a poignant, if predictable, fable about the dangers of denial and the toxic violence inherent to fraternity culture. It's amped up and disturbing, but as an elegantly-placed TV screen in the background of its final seconds indicates, hardly the stuff of fantasy.