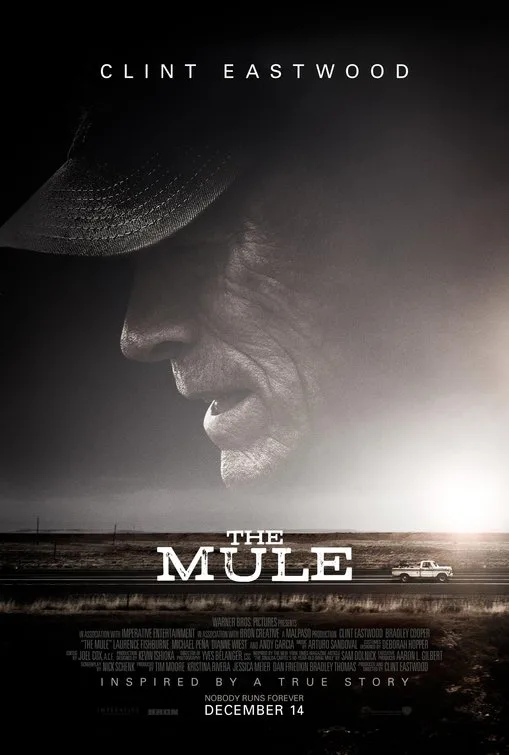

Clint Eastwood's "The Mule," which he directed and stars in, is based on the incredible true story of an octogenarian who became an unlikely drug mule, transporting staggering amounts of cocaine for a major Mexican drug cartel. It features an esteemed cast including Bradley Cooper, Laurence Fishburne, Dianne Wiest and Andy Garcia. And it grapples with several of Eastwood's preferred themes over his legendary career, including regret, forgiveness and the inevitability of mortality.

All the pieces would seem to be in place—on paper at least—for a rich and gripping grown-up drama. So why does the result feel so elusive and unsatisfying? Eastwood's direction is elegant and efficient, as ever. But the script from Nick Schenk ("Gran Torino"), based on a New York Times Magazine article by Sam Dolnick, doesn't give its gifted actors much to work with—and that includes the icon at the film's center.

Eastwood's Earl Stone remains a frustrating enigma, despite being the film's driving force (no pun intended). Could he truly be so naïve at the start as not to know what he's agreeing to carry in the back of his pickup truck? Or does he just not care? After several runs, there's a moment when he finally dares to peek at the contents inside one of the duffel bags that have been packed alongside his golf clubs. He reacts with shock, and that's the end of that. An ethical exploration could have given the story some necessary heft.

Early glimpses of the man in a flashback to 2005 suggest that Earl is a smooth, canny operator, flirting with the adoring, elderly ladies at a daylily convention where the longtime horticulturalist is tantamount to a rock star. He'd also rather party with strangers at a hotel bar than appear at the second wedding of his daughter, Iris (Eastwood's real-life daughter, Alison Eastwood). So perhaps Earl is just really good at compartmentalizing. But even an actor of Eastwood's subtlety and stature has trouble conveying the heart of this complicated man.

12 years later, having suffered the foreclosure of his Illinois flower farm and struggling to stay afloat financially, Earl says yes when a stranger at his granddaughter's bridal brunch hands him a phone number soon after meeting him and suggests he could make a decent amount of cash just by driving. (The connection happens too quickly and feels contrived.)

In a parallel storyline that languidly converges with Earl's, Cooper gets even less to work with as DEA Agent Colin Bates, whose task it is to stem the flow of drugs into the Chicago area. (Fishburne plays his boss.) It would seem impossible to render Cooper—an Oscar nominee for Eastwood's 2014 drama "American Sniper"—charisma-free, but "The Mule" manages to accomplish that dubious feat. Working alongside Michael Pena as his similarly bland partner, Cooper's Agent Bates is coolly, competently focused on his assignment, and that's about the extent of his character development.

The actual back-and-forths between El Paso, Texas, and the generic Midwestern motel where Earl delivers the goods offer some aesthetic pleasures. A stretch through White Sands National Monument is especially striking. (Yves Belanger, a frequent Jean-Marc Vallee collaborator, is the cinematographer.) And each trip steadily builds on the tension of the last as the cargo, stakes, and danger increase. But the journeys also reveal Earl's propensity for doing things his own way, whether it's stopping to eat pulled-pork barbecue sandwiches for lunch with his uptight handlers in tow or staying overnight at a cheap motel and enjoying the company of a couple of ladies for hire.

He's a narcissist until nearly the very end, having estranged himself from his family for decades in favor of working and playing hard on the road. So when he has a sudden change of heart and finally says all the right things to the people he's disappointed for so long—including his bitter ex-wife (Wiest) and his more optimistic granddaughter (Taissa Farmiga)—the moment doesn't quite achieve the emotional resonance it seeks, despite Eastwood's best efforts. Certainly, he knows how to indicate great feeling with just a pained glance, but here he can only do so much. "The Mule" repeatedly spells out and hammers home its message about the importance of family, but it ultimately rings hollow. (The musical choices are also painfully on the nose, ranging from "On the Road Again" to "I've Been Everywhere.")

There's also an icky, creeping sensation of xenophobia that permeates the film. One could imagine "The Mule" being used as an argument in favor of President Trump's proposed border wall, given its tone-deaf and one-dimensional depiction of the minorities Earl encounters. Casually racist, he refers to blacks and Hispanics in good-naturedly antiquated terms. But then all the Mexicans he works for are scary, gun-toting criminals who want to bring drugs into our country, and many of them are depicted in stereotypical fashion with shaved heads and neck tats. They're taking advantage of Earl, a hardworking Korean War veteran who's seen the American Dream collapse beneath him.

Earl is Trump's proverbial Forgotten Man: Elderly, white and living in the Heartland, he listens to country music and longs for a simpler time before the Internet complicated everything. He's in your movie theater today, but you could easily imagine him on Fox News tomorrow.